Forget what you know about good study habits — from the NY Times by Benedict Carey

Take the notion that children have specific learning styles, that some are “visual learners” and others are auditory; some are “left-brain” students, others “right-brain.” In a recent review of the relevant research, published in the journal Psychological Science in the Public Interest, a team of psychologists found almost zero support for such ideas. “The contrast between the enormous popularity of the learning-styles approach within education and the lack of credible evidence for its utility is, in our opinion, striking and disturbing,” the researchers concluded.

…

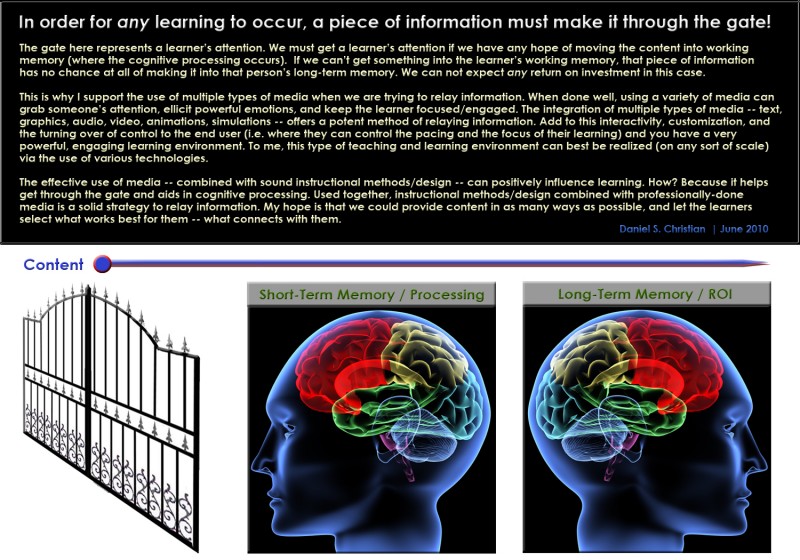

Cognitive scientists do not deny that honest-to-goodness cramming can lead to a better grade on a given exam. But hurriedly jam-packing a brain is akin to speed-packing a cheap suitcase, as most students quickly learn — it holds its new load for a while, then most everything falls out.

“With many students, it’s not like they can’t remember the material” when they move to a more advanced class, said Henry L. Roediger III, a psychologist at Washington University in St. Louis. “It’s like they’ve never seen it before.”

When the neural suitcase is packed carefully and gradually, it holds its contents for far, far longer. An hour of study tonight, an hour on the weekend, another session a week from now: such so-called spacing improves later recall, without requiring students to put in more overall study effort or pay more attention, dozens of studies have found.

No one knows for sure why. It may be that the brain, when it revisits material at a later time, has to relearn some of what it has absorbed before adding new stuff — and that that process is itself self-reinforcing.

From DSC:

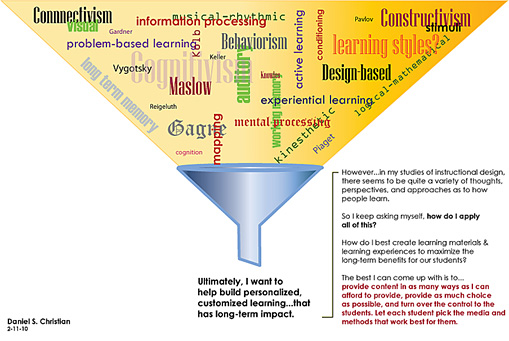

Re: research on learning styles…I would really like to know if these students were interviewed/reviewed in terms of which methods they preferred to learn by…which methods made learning more interesting…more fun..more efficient.

I’ll bet you “good students” can learn in spite of a variety of obstacles, issues, and/or teaching methods…they’ll learn what they need to in order to get the grade.

- But which method(s) do they — as well as less “successful” students — prefer?

- Which methods produce a longer-term ROI (besides just making it past the mid-term or final exam)?

- Which method(s) are more engaging to them?

- Which method(s) take less time for them to absorb the material?

We want students to love learning…but if you don’t like something, you surely won’t love it.