From DSC:

I have often reflected on differentiation or what some call personalized learning and/or customized learning. How does a busy teacher, instructor, professor, or trainer achieve this, realistically?

It’s very difficult and time-consuming to do for sure. But it also requires a team of specialists to achieve such a holy grail of learning — as one person can’t know it all. That is, one educator doesn’t have the necessary time, skills, or knowledge to address so many different learning needs and levels!

- Think of different cognitive capabilities — from students that have special learning needs and challenges to gifted students

- Or learners that have different physical capabilities or restrictions

- Or learners that have different backgrounds and/or levels of prior knowledge

- Etc., etc., etc.

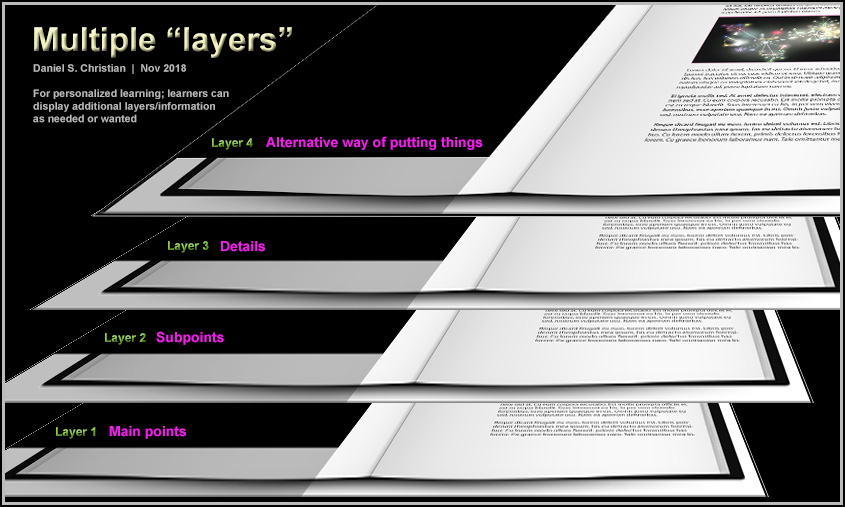

Educators and trainers have so many things on their plates that it’s very difficult to come up with _X_ lesson plans/agendas/personalized approaches, etc. On the other side of the table, how do students from a vast array of backgrounds and cognitive skill levels get the main points of a chapter or piece of text? How can they self-select the level of difficulty and/or start at a “basics” level and work one’s way up to harder/more detailed levels if they can cognitively handle that level of detail/complexity? Conversely, how do I as a learner get the boiled down version of a piece of text?

Well… just as with the flipped classroom approach, I’d like to suggest that we flip things a bit and enlist teams of specialists at the publishers to fulfill this need. Move things to the content creation end — not so much at the delivery end of things. Publishers’ teams could play a significant, hugely helpful role in providing customized learning to learners.

Some of the ways that this could happen:

Use an HTML like language when writing a textbook, such as:

<MainPoint> The text for the main point here. </MainPoint>

<SubPoint1>The text for the subpoint 1 here.</SubPoint1>

<DetailsSubPoint1>More detailed information for subpoint 1 here.</DetailsSubPoint1>

<SubPoint2>The text for the subpoint 2 here.</SubPoint2>

<DetailsSubPoint2>More detailed information for subpoint 2 here.</DetailsSubPoint2>

<SubPoint3>The text for the subpoint 3 here.</SubPoint3>

<DetailsSubPoint3>More detailed information for subpoint 3 here.</DetailsSubPoint1>

<SummaryOfMainPoints>A list of the main points that a learner should walk away with.</SummaryOfMainPoints>

<BasicsOfMainPoints>Here is a listing of the main points, but put in alternative words and more basic ways of expressing those main points. </BasicsOfMainPoints>

<Conclusion> The text for the concluding comments here.</Conclusion>

<BasicsOfMainPoints> could be called <AlternativeExplanations>

Bottom line: This tag would be to put things forth using very straightforward terms.

Another tag would be to address how this topic/chapter is relevant:

<RealWorldApplication>This short paragraph should illustrate real world examples

of this particular topic. Why does this topic matter? How is it relevant?</RealWorldApplication>

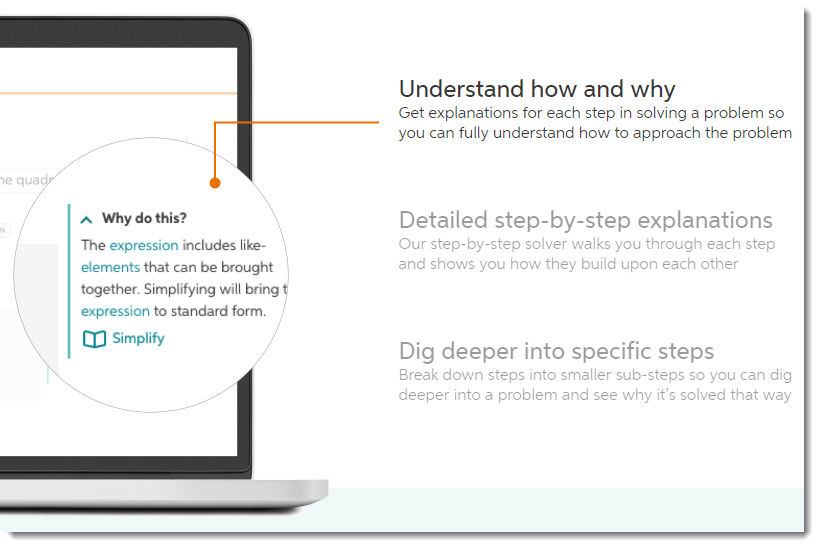

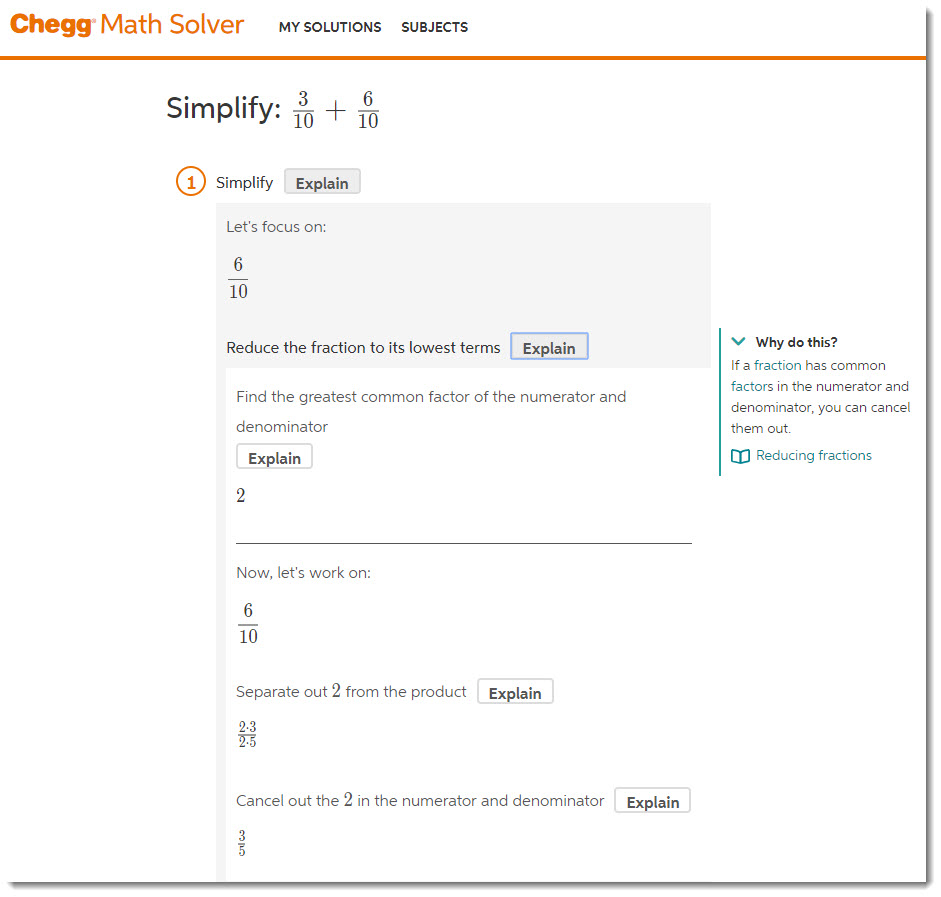

On the students’ end, they could use an app that works with such tags to allow a learner to quickly see/review the different layers. That is:

- Show me just the main points

- Then add on the sub points

- Then fill in the details

OR

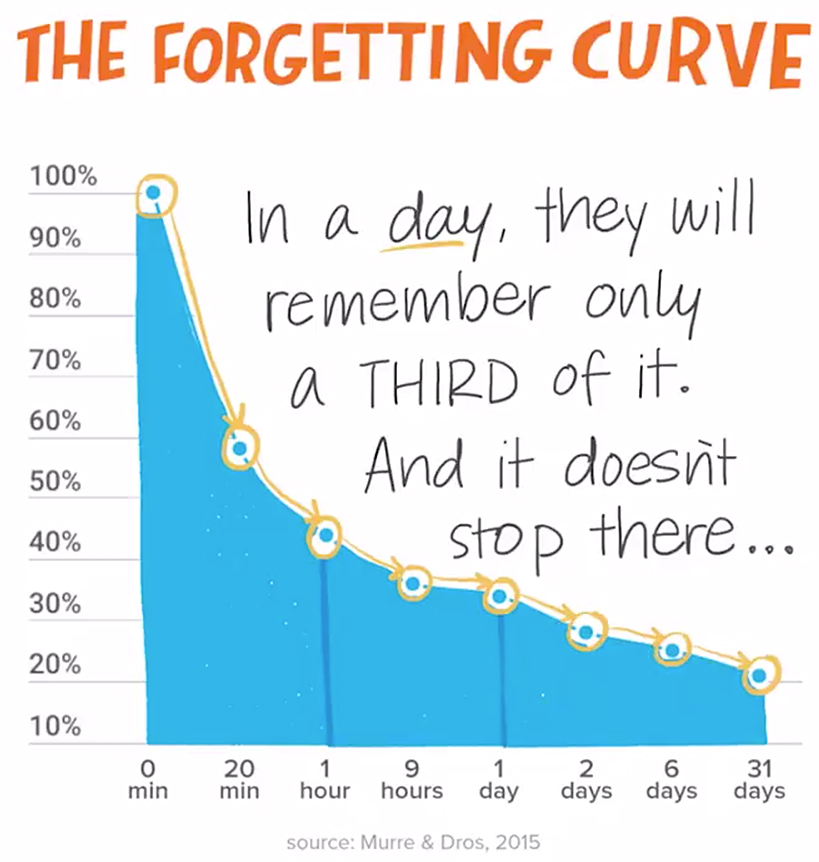

- Just give me the basics via an alternative ways of expressing these things. I won’t remember all the details. Put things using easy-to-understand wording/ideas.

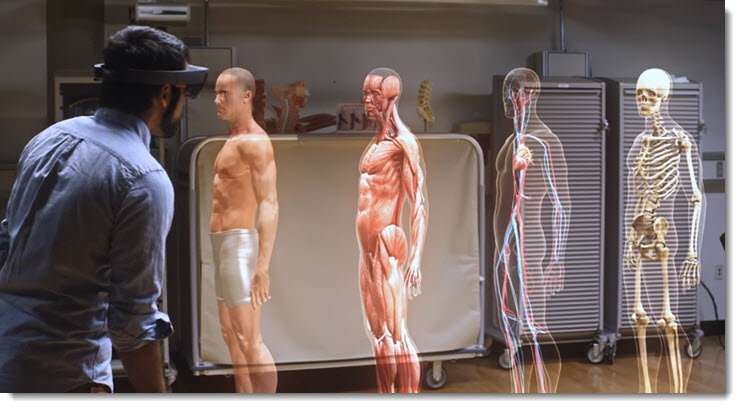

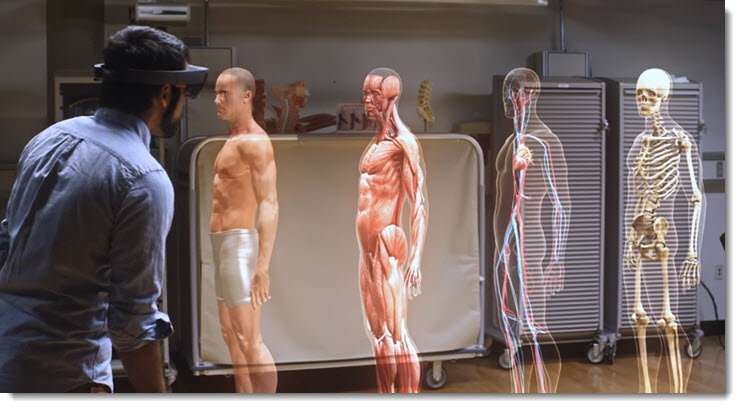

It’s like the layers of a Microsoft HoloLens app of the human anatomy:

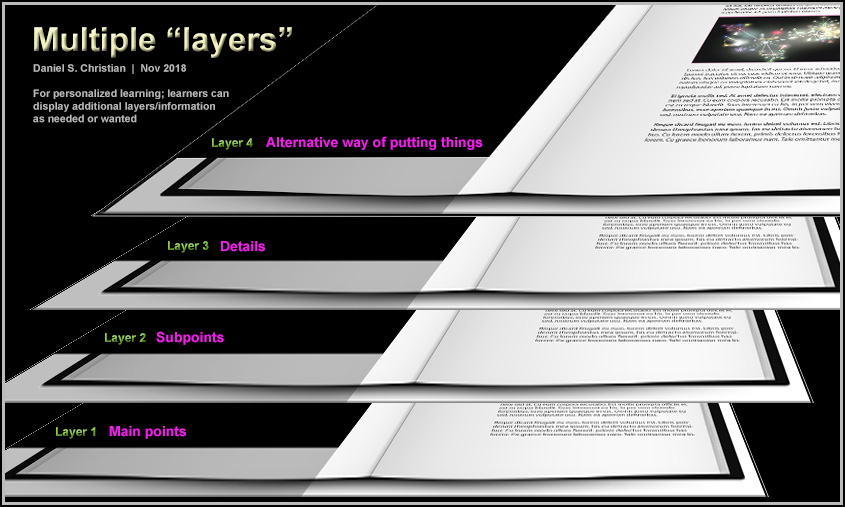

Or it’s like different layers of a chapter of a “textbook” — so a learner could quickly collapse/expand the text as needed:

This approach could be helpful at all kinds of learning levels. For example, it could be very helpful for law school students to obtain outlines for cases or for chapters of information. Similarly, it could be helpful for dental or medical school students to get the main points as well as detailed information.

Also, as Artificial Intelligence (AI) grows, the system could check a learner’s cloud-based learner profile to see their reading level or prior knowledge, any IEP’s on file, their learning preferences (audio, video, animations, etc.), etc. to further provide a personalized/customized learning experience.

To recap:

- “Textbooks” continue to be created by teams of specialists, but add specialists with knowledge of students with special needs as well as for gifted students. For example, a team could have experts within the field of Special Education to help create one of the overlays/or filters/lenses — i.e., to reword things. If the text was talking about how to hit a backhand or a forehand, the alternative text layer could be summed up to say that tennis is a sport…and that a sport is something people play. On the other end of the spectrum, the text could dive deeply into the various grips a person could use to hit a forehand or backhand.

- This puts the power of offering differentiation at the point of content creation/development (differentiation could also be provided for at the delivery end, but again, time and expertise are likely not going to be there)

- Publishers create “overlays” or various layers that can be turned on or off by the learners

- Can see whole chapters or can see main ideas, topic sentences, and/or details. Like HTML tags for web pages.

- Can instantly collapse chapters to main ideas/outlines.