From DSC:

Low-stakes formative assessments offer enormous benefits and should be used extensively throughout K-12, higher education, L&D/corporate universities, in law schools, medical schools, dental schools, and more.

Below are my notes from the following article – with the provided emphasis/bolding/highlighting via colors, etc. coming from me:

Duhart, Olympia. “The “F” Word: The Top Five Complaints (and Solutions) About Formative Assessment.” Journal of Legal Education, vol. 67, no. 2 (winter 2018), pp. 531-49. <– with thanks to Emily Horvath, Director of Academic Services & Associate Professor, WMU-Cooley Law School

“No one gets behind the wheel of a car for the first time on the day of the DMV road test. People know that practice counts.” (p. 531)

“Yet many law professors abandon this common-sense principle when it comes to teaching law students. Instead of providing multiple opportunities for practice with plenty of space to fail, adjust, and improve, many law school professors place almost everything on a single high-stakes test at the end of the semester.” (p. 531)

“The benefits of formative assessment are supported by cognitive science, learning theory, legal education experts, and common sense. An exhaustive review of the literature on formative assessment in various schools settings has shown that it consistently improves academic performance.” (p. 544)

ABA’s new formative assessment standards (see pg 23)

An emphasis on formative assessments, not just a mid-term and/or a final exam – which are typically called “summative assessments.”

“The reliance on a single high-stakes exam at the end of the semester is comparable to taking the student driver straight to the DMV without spending any time practicing behind the wheel of a car. In contrast, formative assessment focuses on a feedback loop. It provides critical information to both the students and instructor about student learning.” (p. 533)

“Now a combination of external pressure and a renewed focus on developing self-regulated lawyers has brought formative assessment front and center for law schools.” (p. 533)

“In fall 2016, the ABA implemented new standards that require the use of formative assessment in law schools. Standard 314 explicitly requires law schools to use both formative and summative assessment to “’measure and improve’ student learning.” (pgs. 533-534)

Standard 314. ASSESSMENT OF STUDENT LEARNING

A law school shall utilize both formative and summative assessment methods in its curriculum to measure and improve student learning and provide meaningful feedback to students.

Interpretation 314-1

Formative assessment methods are measurements at different points during a particular course or at different points over the span of a student’s education that provide meaningful feedback to improve student learning. Summative assessment methods are measurements at the culmination of a particular course or at the culmination of any part of a student’s legal education that measure the degree of student learning.

Interpretation 314-2

A law school need not apply multiple assessment methods in any particular course. Assessment methods are likely to be different from school to school. Law schools are not required by Standard 314 to use any particular assessment method.

From DSC:

Formative assessments use tests as a learning tool/strategy. They help identify gaps in students’ understanding and can help the instructor adjust their teaching methods/ideas on a particular topic. What are the learners getting? What are they not getting? These types of assessments are especially important in the learning experiences of students in their first year of law school. All students need feedback, and these assessments can help give them feedback as to how they are doing.

Practice. Repetition. Feedback. <– all key elements in providing a solid learning experience!

“…effective assessment practices are linked to the development of effective lawyers.” (pg. 535)

“Low-risk formative assessment give students multiple opportunities to make mistakes and actively engage with the material they are learning.” (p. 537)

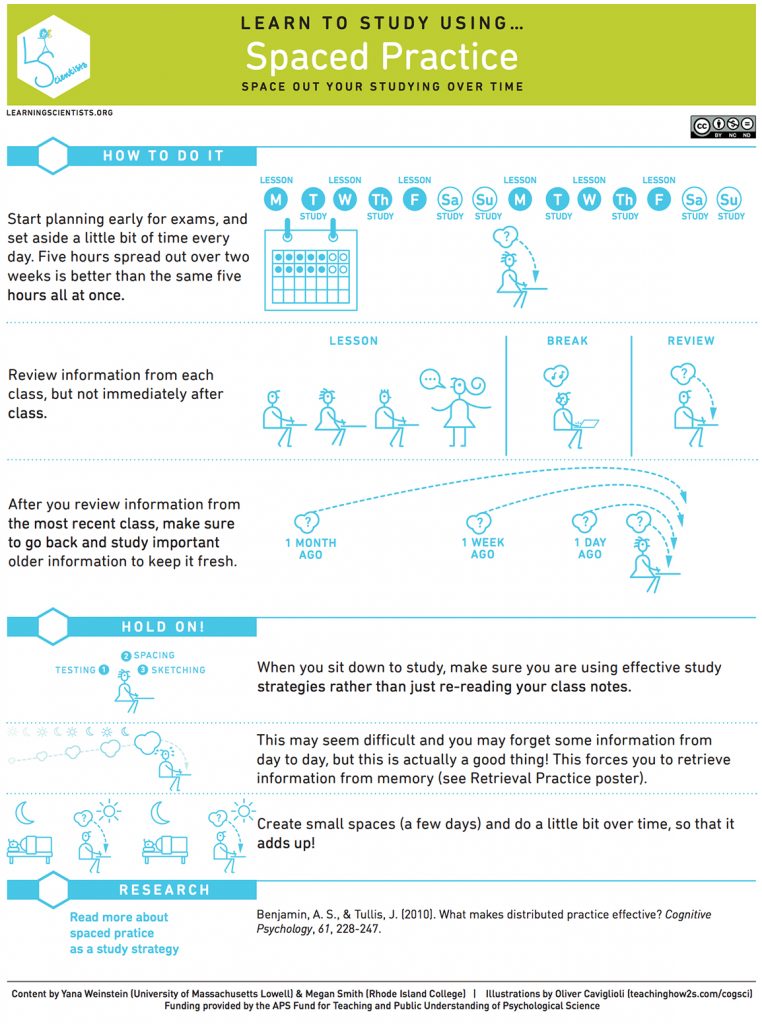

Formative assessments force the students to practice recall. This is very helpful in terms of helping students actually remember the information. The spaced out practice of forcing recall – no matter how much the struggle of recalling it – aids in retaining information and moving items into longer-term memory. (See Make It Stick: The Science of Successful Learning by Peter C. Brown, Henry L. Roediger III, & Mark A. McDaniel). In fact, according to this book’s authors, the more the struggle in recalling the information, the greater the learning.

Formative assessments can help students own their own learning. Self-regulation. Provide opportunities for students to practice meta-cognition – i.e., thinking about their thinking.

“Lawyers need to be experts at self-regulated learning.” (p. 541)

The use of numerous, low-stakes quizzes and more opportunities for feedback reduces test anxiety and can help with the mental health of students. Can reduce depression and help build a community of learners. (p. 542)

“Millennials prefer interactive learning opportunities, regular assessments, and immediate feedback.” (p. 544)

Ideas:

- As a professor, you don’t have to manually grade every formative assessment. Technology can help you out big time. Consider building a test bank of multiple-choice questions and then drawing upon them to build a series of formative assessments. Have the technology grade the exams for you.

- Digital quizzes using Blackboard Learn, Canvas, etc.

- Tools like Socrative

- Alternatively, have the students grade each other’s work or their own work. Formative assessments don’t have to be graded or count towards a grade. The keys are in learners practicing their recall, checking their own understanding, and, for the faculty member, perhaps pointing out the need to re-address something and/or to experiment with one’s teaching methods.

- Consider the use of rubrics to help make formative assessments more efficient. Rubrics can relay the expectations of the instructors on any given assignment/assessment. Rubrics can also help TA’s grade items or even the students in grading each other’s items.

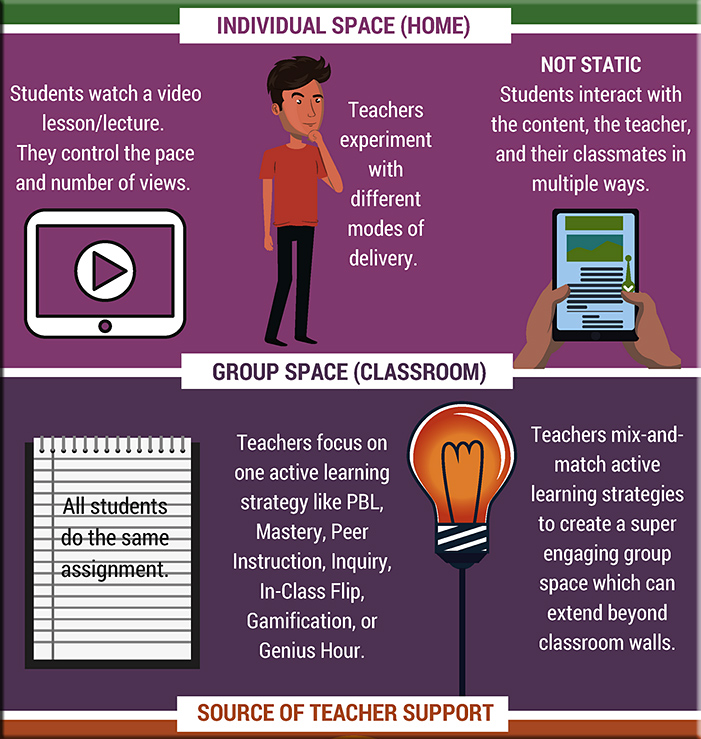

- Formative assessments don’t have to be a quiz/test per se. They can be games, presentations, collaborations with each other.

For further insights on this topic (and more) from Northwestern University, see:

New ABA Requirements Bring Changes to Law School Classrooms, Creating Opportunity, and Chaos –from blog.northwesternlaw.review by Jacob Wentzel

Excerpt:

Unbeknownst to many students J.D. and L.L.M. students, our classroom experiences are embarking upon a long-term path toward what could be significant changes as a trio of ABA requirements for law schools nationwide begin to take effect.

The requirements are Standards 302, 314, and 315 , each of which defines a new type of requirement: learning outcomes (302), assessments (314), and global evaluations of these (315). According to Christopher M. Martin, Assistant Dean and Clinical Assistant Professor at Northwestern Pritzker School of Law, these standards take after similar ones that the Department of Education rolled out for undergraduate universities years ago. In theory, they seek to help law schools improve their effectiveness by, among other things, telling students what they should be learning and tracking students’ progress throughout the semester. Indeed, as a law student, it often feels like you lose the forest for the trees, imbibing immense quantities of information without grasping the bigger picture, let alone the skills the legal profession demands.

…

By contrast, formative assessment is about assessing students “at different points during a particular course,” precisely when many courses typically do not. Formative assessments are also about generating information and ideas about what professors do in the classroom. Such assessment methods include quizzes, midterms, drafts, rubrics, and more. Again, professors are not required to show students the results of such assessments, but must maintain and collect the data for institutional purposes—to help law schools track how students are learning material during the semester and to make long-term improvements.

And/or see a Google query on “ABA new formative assessment standards”