The Lesson You Never Got Taught in School: How to Learn! — from bigthink.com by Simon Oxenham (from 2/15/13)

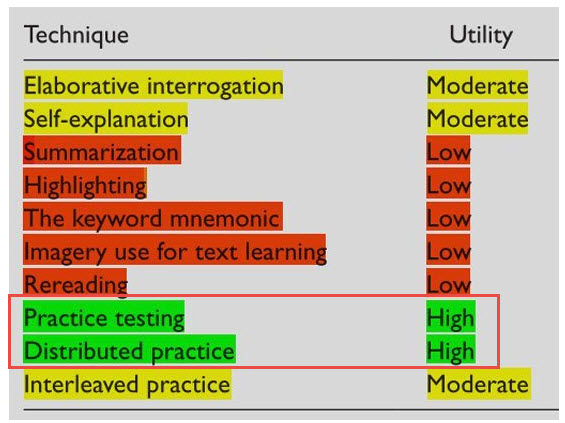

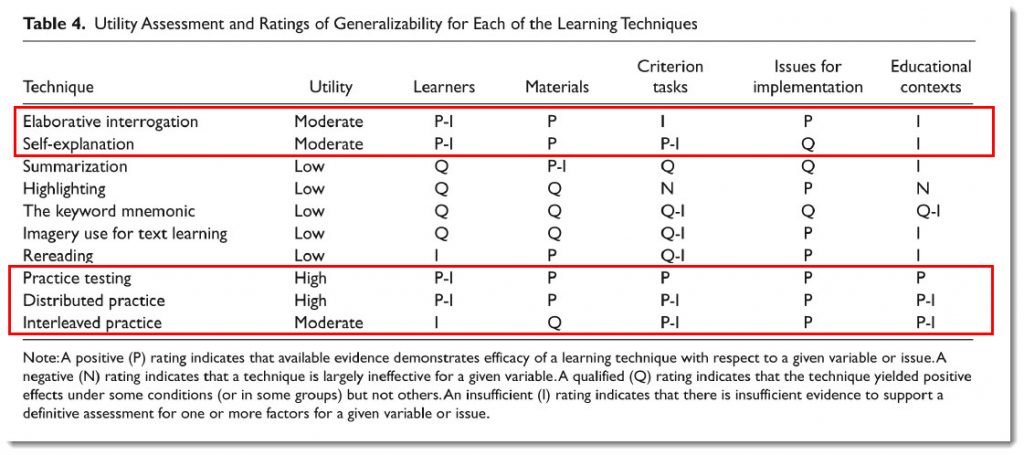

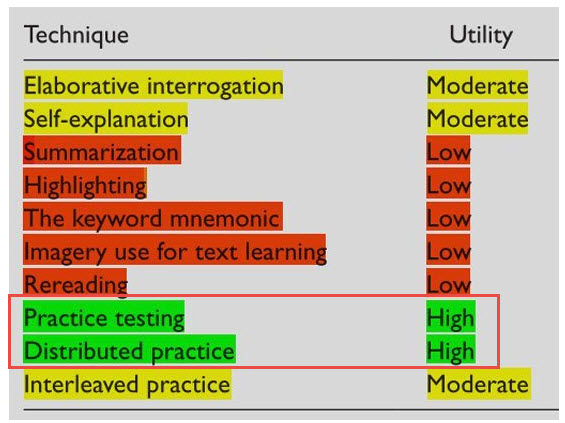

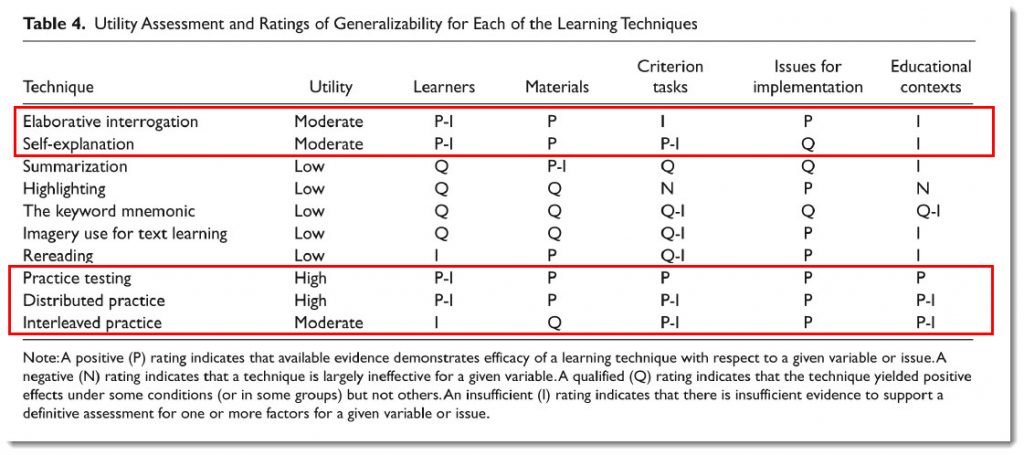

Psychological Science in the Public Interest evaluated ten techniques for improving learning, ranging from mnemonics to highlighting and came to some surprising conclusions.

Excerpts:

Practice Testing (Rating = High)

This is where things get interesting; testing is often seen as a necessary evil of education. Traditionally, testing consists of rare but massively important ‘high stakes’ assessments. There is however, an extensive literature demonstrating the benefits of testing for learning – but importantly, it does not seem necessary that testing is in the format of ‘high stakes’ assessments. All testing including ‘low stakes’ practice testing seems to result in benefits. Unlike many of the other techniques mentioned, the benefits of practice testing are not modest – studies have found that a practice test can double free recall!

Distributed Practice (Rating = High)

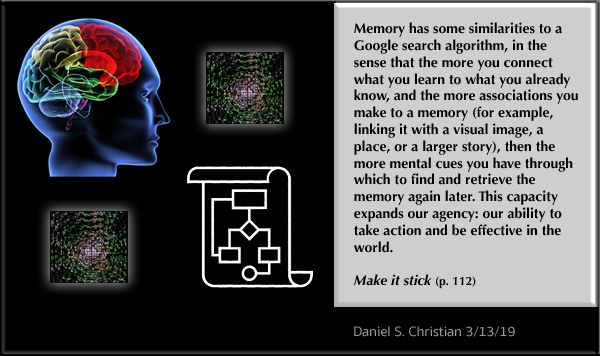

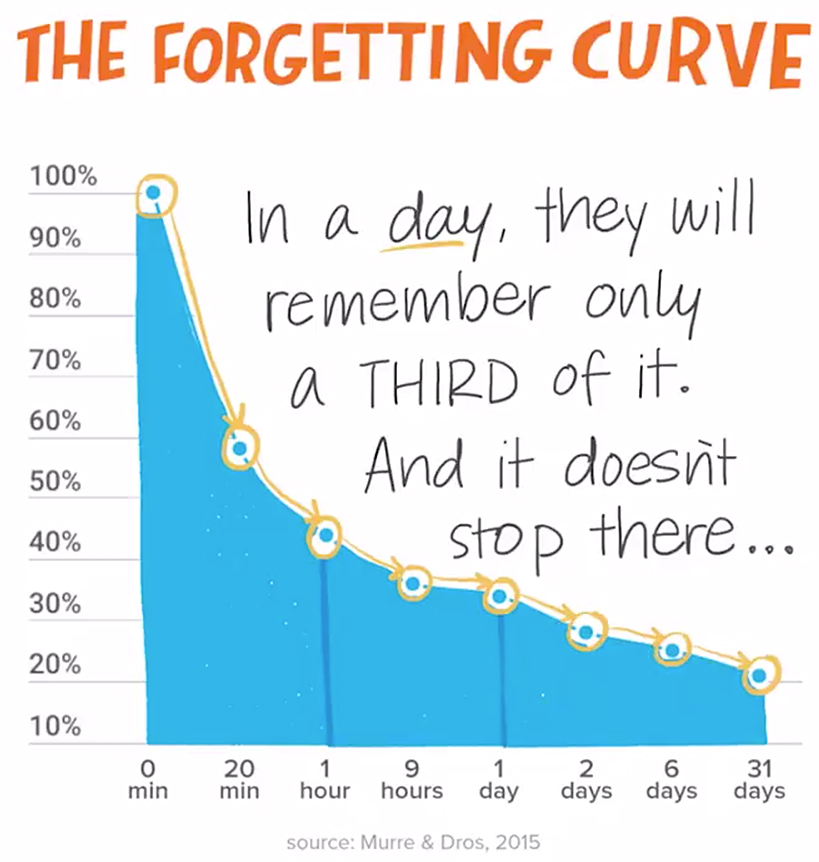

Have you ever wondered whether it is best to do your studying in large chunks or divide your studying over a period of time? Research has found that the optimal level of distribution of sessions for learning is 10-20% of the length of time that something needs to be remembered. So if you want to remember something for a year you should study at least every month, if you want to remember something for five years you should space your learning every six to twelve months. If you want to remember something for a week you should space your learning 12-24 hours apart. It does seem however that the distributed-practice effect may work best when processing information deeply – so for best results you might want to try a distributed practice and self-testing combo.

Also see:

Per Willingham (emphasis DSC):

- Rereading is a terribly ineffective strategy. The best strategy–by far — is to self-test — which is the 9th most popular strategy out of 11 in this study. Self-testing leads to better memory even compared to concept mapping (Karpicke & Blunt, 2011).

Three Takeaways from Becoming An Effective Learner:

- Boser says that the idea that people have different learning styles, such as visual learning or verbal learning, has little scientific evidence to support it.

- According to Boser, teachers and parents should praise their kids’ ability and effort, instead of telling them they’re smart. “When we tell people they are smart, we give them… a ‘fixed mindset,’” says Boser.

- If you are learning piano – or anything, really – the best way to learn is to practice different composers’ work. “Mixing up your practices is far more effective,” says Boser.

Cumulative exams aren’t the same as spacing and interleaving. Here’s why. — from retrievalpractice.org

Excerpts (emphasis DSC):

Our recommendations to make cumulative exams more powerful with small tweaks for you and your students:

- Cumulative exams are good, but encourage even more spacing and discourage cramming with cumulative mini-quizzes throughout the semester, not just as an end-of-semester exam.

- Be sure that cumulative mini-quizzes, activities, and exams include similar concepts that require careful discrimination from students, not simply related topics.

- Make sure you are using spacing and interleaving as learning strategies and instructional strategies throughout the semester, not simply as part of assessments and cumulative exams.

Bottom line: Just because an exam is cumulative does not mean it automatically involves spacing or interleaving. Be mindful of relationships across exam content, as well as whether students are spacing their study throughout the semester or simply cramming before an exam – cumulative or otherwise.

From DSC:

We, like The Learning Scientists encourages us to do and even provides their own posters, should have posters with these tips on them throughout every single school and library in the country. The posters each have a different practice such as:

- Spaced practice

- Retrieval practice

- Elaboration

- Interleaving

- Concrete examples

- Dual coding

That said, I could see how all of that information could/would be overwhelming to some students and/or the more technical terms could bore them or fly over their heads. So perhaps we could boil down the information to feature excerpts from the top sections only that put the concepts into easier to digest words such as:

- Practice bringing information to mind

- Switch between ideas while you study

- Combine words and visuals

- Etc.