Employment & Sustainability: Report of the Cornell ILR School 2013 Roundtable on Employment and Technology — from ilr.cornell.edu

Excerpt:

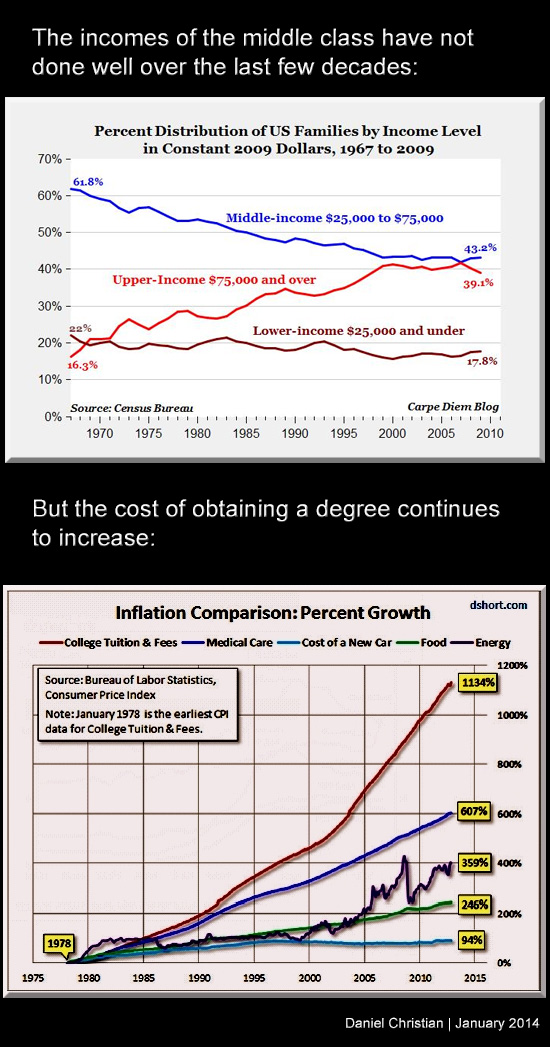

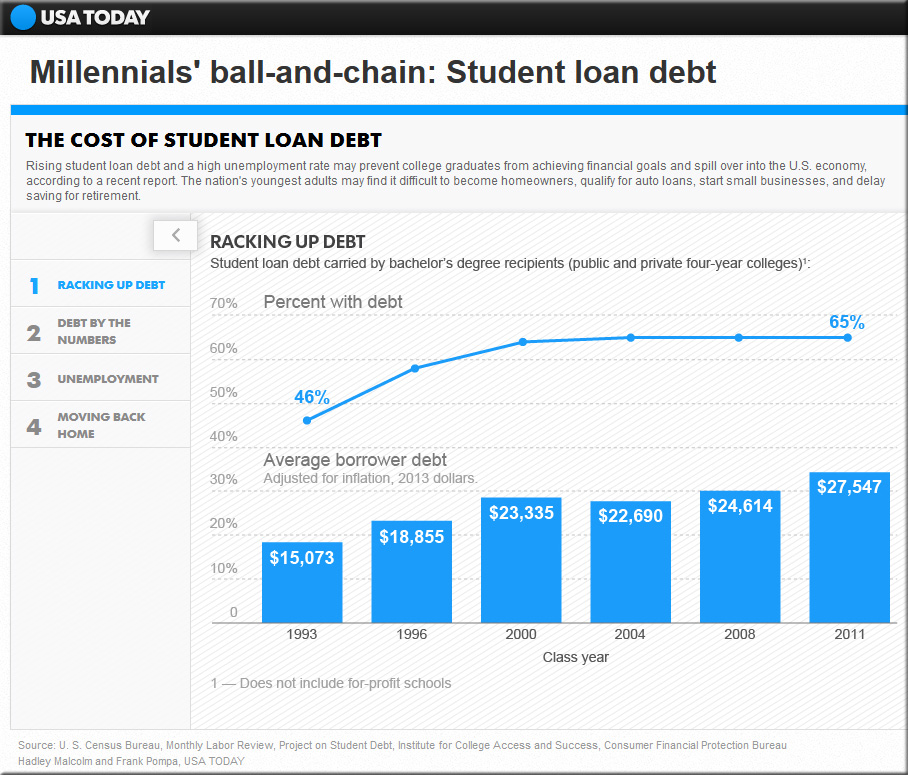

The Great Recession has compounded the ongoing forces of technological change and globalization to drive an even more profound transformation in the relationships between Americans and work. Jobs are disappearing, skill sets are a moving target and the evolving concept of earning a sustainable living is becoming increasingly complex and, for many, increasingly remote.

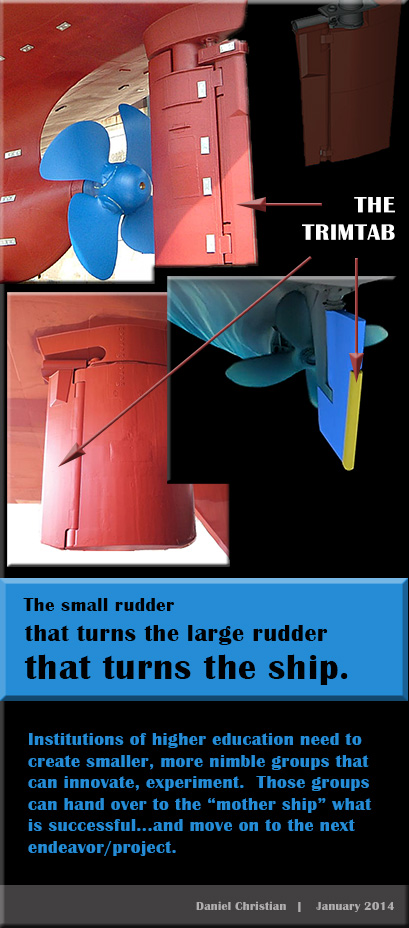

The Cornell ILR School, a renowned leader in advancing the world of work, recognizes that today’s and tomorrow’s challenges demand a new paradigm, one that joins together the many highly educated – but also siloed – discussions about employers’ use of new technologies and the impact on quality job creation.

On April 12, 2013, the ILR School convened 40 economists and engineers, academics and corporate executives, social scientists and philanthropists, policy makers and journalists and statisticians in a ground-breaking, cross-sector, invitation-only dialogue. It was a day full of agreement, fervently diverse opinions and insights – notably that most participants had never before discussed these issues with such a varied group of stakeholders, and that the country’s best hope for reaping widespread gains from technological progress rests on continuing and expanding such discourse.

Also see:

Should we fear “the end of work”? — from pbs.org by Frank Koller

Excerpts (emphasis DSC):

Key points raised and addressed:

- Technological advancement and globalization are significantly impacting U.S. jobs and raising the risk that more and more U.S. workers will be caught “in the middle” as jobs migrate to higher-skill and lower-skill work.

- Collection of U.S. economic data for measuring work and the labor market is not keeping pace with the rapidly changing world of work.

- As globalization and technology make it more efficient for companies to engage fewer U.S. workers, and more of them in countries such as India and China, these forces are also changing the U.S. innovation advantage.

- Current conceptualization of Corporate Social Responsibility isn’t enough.

Overall, there was widespread agreement that a much broader and more vigorous national discussion is needed regarding the short- and longer-term impacts of technological advances on the nature of work, the creation and elimination of jobs, and the ability of U.S. workers to earn a sustainable living.

…

“There is a real need for corporate leadership, and there is a need for accountability. When companies engage in productivity layoffs with record profitability, unprecedented levels of cash and all-time-high stock prices, no one in the media says, ‘Isn’t this terrible?’ No political leader speaks up to protest. We don’t hear anything from the labor unions. The companies are applauded for it because they’re cutting costs and improving profitability, and that’s supposedly what a company exists for. But it’s not that simple. They do have other responsibilities.”

…

“In terms of a market failure, it’s the reality that it’s not in the interests of any individual firm in the United States to try to solve the jobs problem. So, we’ve got to figure out a way to deal with that…and the only way that you solve this is by getting people and institutions and organizations to work together, to engage these issues collectively.

“It’s about an institutional failure over the last 30 years. With the decline of the labor movement, you’ve seen a lot of institutions go downhill equivalently. We don’t see the kind of dialogue, we don’t see the enforcement of our social norms and social policies that discipline corporations, and that really provided the kind of collective spreading of wage patterns and wage norms across the society.

“We’ve got to rebuild those, but we can’t try to rebuild them in an old-fashioned way. Now we’re in a more digital economy, a more knowledge-based economy, and we need to invent the new institutions that will cut across and aggregate these interests to address these challenges. We’ve got to get the education community working with business and employers, working with labor and civil society.

“I’m not a believer that technology is going to naturally eliminate jobs and cut income, but if we don’t do anything about it, if we just leave it, as we have, to individual market forces and to individual corporate actions and to individual technology innovations, then that’s probably where we are headed.