Differentiating learning by ‘learning style’ might not be so wise — from Clayton Christensen

First, some quotes from Clayton:

A study commissioned by Psychological Science in the Public Interest called “Learning Styles: Concepts and Evidence,” by Harold Pashler, Mark McDaniel, Doug Rohrer, and Robert Bjork, finds convincingly that, at this point, there is no evidence that teaching to different learning styles—specifically meaning to a student’s apparent preferred modality such as visual or auditory—works. The authors therefore conclude that using scarce school funds toward doing just this doesn’t make sense.

Of course, there appears to still be some disagreement. According to a March 25, 2009 article in The Journal of Neuroscience titled “The Neural Correlates of Visual and Verbal Cognitive Styles” by David J.M. Kraemer, Lauren M. Rosenberg, and Sharon L. Thompson-Schill, there is some evidence that teaching by learning style could make a difference.

Moving outside of this particular debate, this doesn’t change the fundamental point that people learn differently. People don’t disagree with this. There is clear evidence that that people learn at different paces. Some people understand a concept quickly. Others struggle with it for some time before they understand it. We know that explaining a concept one way works well for some people, and explaining it another way works for others whereas it baffles the first group. We also know that this can differ from person to person depending on subject area. One of the key reasons online learning seems to be better on average than face-to-face learning is because time can become variable in an online learning environment so that students can repeat units and lectures until they master a concept and only then move on to the next concept.

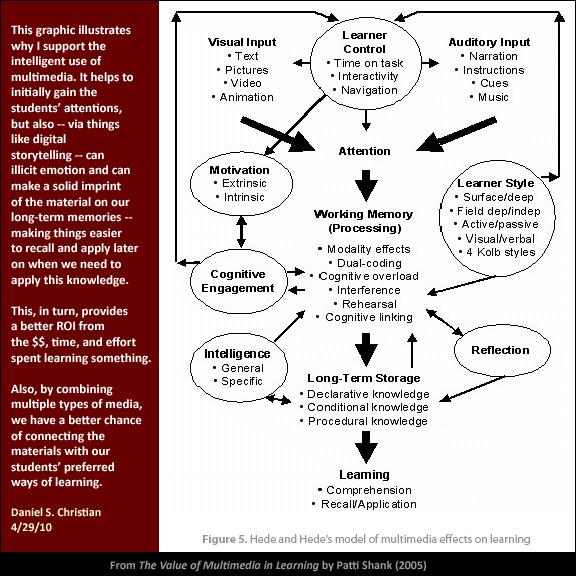

From DSC:

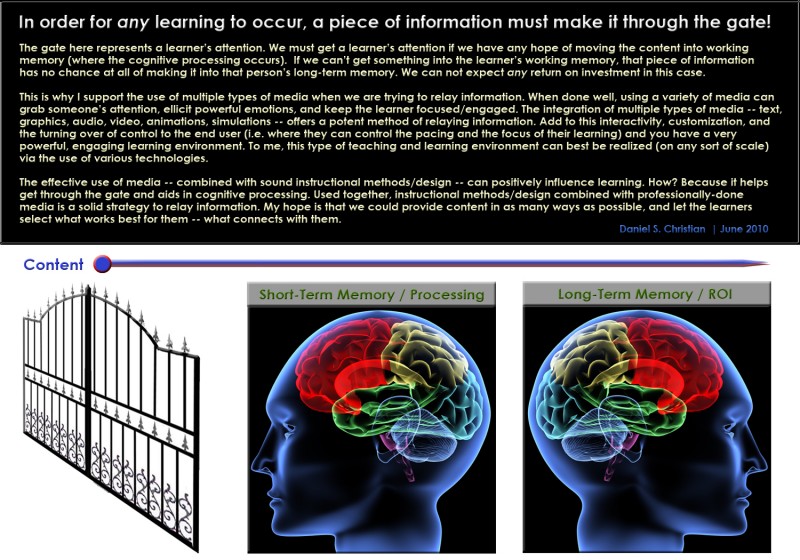

What’s the best way(s) to apply all of this? What makes the most sense in how we operationalize the delivery of our content? In my studies on instructional design, there are so many theories and so much disagreement as to how people learn. If you ask for consensus, you won’t get it. So my conclusion is this:

Provide the same content in as many different ways as you possibly can afford to provide. Let the students choose which item(s) work best for them and connect with them. If one way doesn’t connect, perhaps another one will.

Also…yes, we can probably all learn from just text if we have to. But was learning fun that way? Was it engaging? Was it the most effective it could have been? Was learning maximized for the long-haul? Would it have been helpful to see the same content in a graphic, simulation, animation, or in a video?