The Eight-Minute Lecture Keeps Students Engaged — from facultyfocus.com by Illysa Izenberg; with thanks to Ove Christensen for mentioning this on his paper.li-based e-newsletter

Excerpt:

Numerous studies have demonstrated that students retain little of our lectures, and research on determining the “average attention span,” while varying, seems to congregate around eight to ten minutes (“Attention Span Statistics,” 2015), (Richardson, 2010). Research discussed in a 2009 Faculty Focus article by Maryellen Weimer questions the attention span research, while encouraging instructors to facilitate student focus.

When I began teaching in 2006, I assumed that students could read anything I say. Therefore, my classes consisted of debates of, activities building on, and direct application of theories taught in the readings—no lectures.

But I noticed that students had difficulty understanding the content in a way that enabled accurate and deep application without some framing from me. In short, I needed to lecture—at least a little. This is when I began the eight-minute lecture. If you’re worried that eight minutes is too long, I discovered that when students experience many short lectures throughout the semester, they learn to focus in those bursts, in part because they know the lecture will be brief.

How to implement the eight-minute lecture…

From DSC:

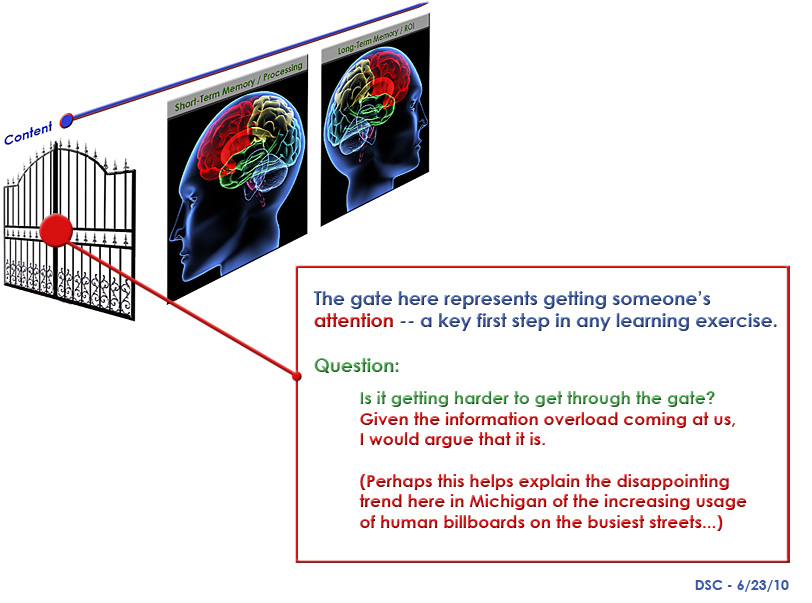

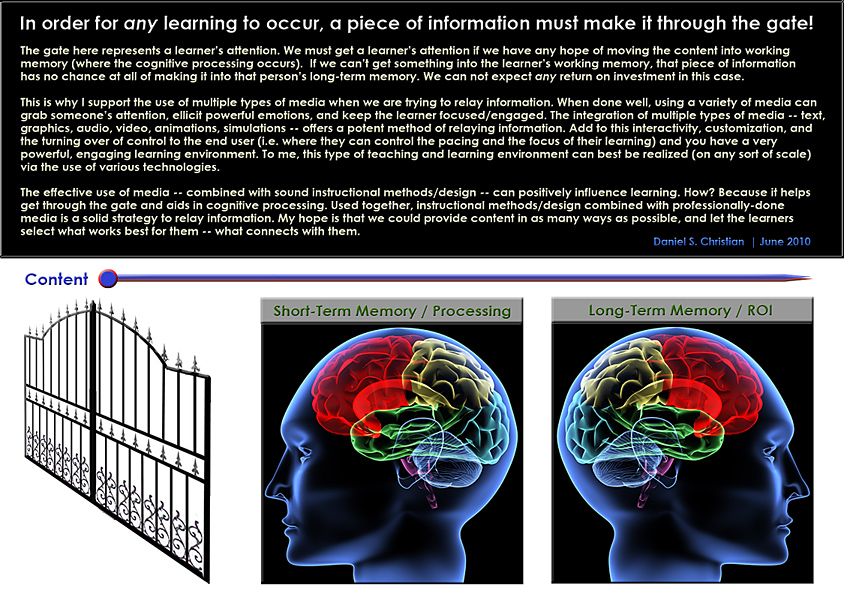

This reminds me of a graphic I did back in 2010, asking, “Is it getting harder to get through the gate?”

Also:

Also, this reminds me of the growing trend that’s occurring across the United States of implementing makerspaces and more active learning-based classrooms — i.e., creating collaborative, participatory learning environments.