Excerpt from Digital Dilemmas: The Data Deluge, Attention Deficits and The Future of Books

Given people are creating and receiving an exponentially growing amount of information per day and time is not expanding, author Adrian Ott on Fast Company suggests we are in an “attention arms race.” (emphasis DSC) Despite the massive information processing power of the human brain, the senior executives we work with confirm this challenge. Even with faster computers and an ever-expanding array of mobile devices to receive and process information anytime, anywhere, people struggle to keep up. Often we try to multitask, but according to McKinsey on information overload, multitasking is not productive or creative.

From DSC:

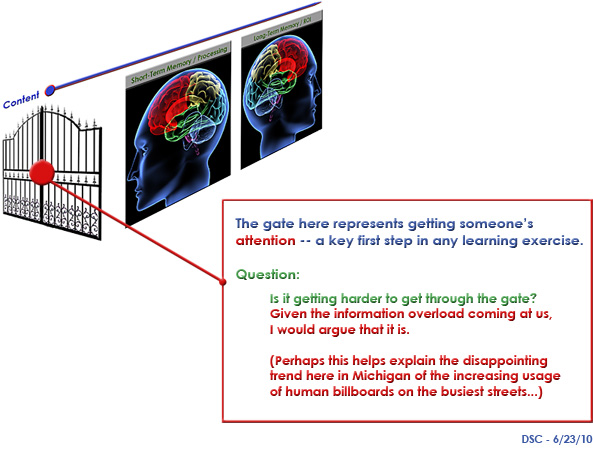

This is why I think it is getting — and will continue to get — harder to get someone’s attention (i.e. getting through what I call “the gate”); and if I can’t get through the gate, I can’t make it into someone’s short-term or working memory. If that’s the case, I have zero chance of getting into their long-term memory (i.e. zero return on investment.)

This is not only true for students, but I believe that it’s true for everyone. For example, how many human billboards (waiving some type of signage or wearing some type of clothing/costume) have you seen recently? I see 1-2 a day. I created the graphic last summer to illustrate this potential issue:

Some of my proposed solutions to this issue include:

- Help students identify and tap into their passions — writing, video editing, photography, singing, acting, acting as a copyright expert, subject matter researcher, etc.

- Use digital storytelling

- Use educational technologies that engage (iPads, interactive whiteboards, Garageband, etc.)

- Keep everything brief — chunk content up into bite-sized pieces

- Offer students a choice of assignments, media and let them select what they prefer to work with

- Offer content feeds that are engaging in order to keep content constantly streaming into a student’s short-term memory; over time, the main points make their way into the student’s long-term memory