Why demand originality from students in online discussion forums? — from facultyfocus.com by Ronald Jones

Excerpt:

Tell me in your own words

Why demand originality? In relating to a traditional classroom discussion, do students respond to the professor’s question by opening up the textbook or searching for the answer on the Internet and then reading off the answer? Some might try, but by asking questions the professor is looking to see if the students grasp the discussed concept, not if they know how and where to find the answer.

Online students have the advantage of reflection time, along with having the textbook and Internet search engine open when responding to discussion questions. With a few simple clicks, virtually any question can be answered by searching the Internet. Once again, why demand originality? Classroom learning takes place when students are required to think; that’s a few steps beyond clicking copy and paste. As instructors, we should encourage our students to be resourceful and to learn the skills of locating and incorporating scholarly literature into their work. But we also must instill the learning value of synthesizing sources in such a manner that produces evidence of gained knowledge.

From DSC:

I like the idea of asking students to put it into their own words. Not just to get by the issue of copying/pasting or trying to stem plagiarism, but because it’s more along the line of journaling about our learning. We need to actually engage with some content in order to put that content into our own words. Not outsourcing our learning to others. Journaling can help us clarify what we’re understanding and where we still have questions and/or concerns.

Encouraging participation of all in the course: Moving from intact classes to individuals students — from scholarlyteacher.com by Todd Zakrajsek, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill

Excerpts:

During every class session, read the room by watching individuals. Are students taking notes, nodding along as others speak, or even advancing the discussion by building on the comments of classmates? Are verbal responses merely defining terminology, or do they make connections between the text and real-world examples? Analyze the extent to which certain examples or content areas are received by individual students. Take note when student responses are merely noise to fill the void when you are not talking. Overall, look for individual characteristics that emerge within your course as a community of learning is being established.

…

Keep in mind that it is often less threatening to one’s ego to claim a lack of preparation for class than it is to admit that one is finding it difficult to understand the material. For those who need a bit of motivation to come prepared, a quiz at the beginning of class will help students to come to class ready to discuss the material for that day.

…

As all students are pressed for time these days, a quiz might be the added motivation that most students need. These quizzes do not need to be extremely challenging, but they should be challenging enough to ensure the required preparation is done. That is, one should not be able to get responses correct simply by guessing. For students who do not understand the material, quizzes will not prepare them to engage in class discussions or to answer your questions during a discussion lecture. For those students, failed quizzes might add additional pressure and cause less engagement with the material. Struggling students who are not prepared for class need assistance to understand the material. Carefully structured small group projects and discussions might be the best way to get their voices into the class. Ask increasingly difficult questions as part of the discussion, and when you know you have struggling students reserve some of the easier questions for those students.

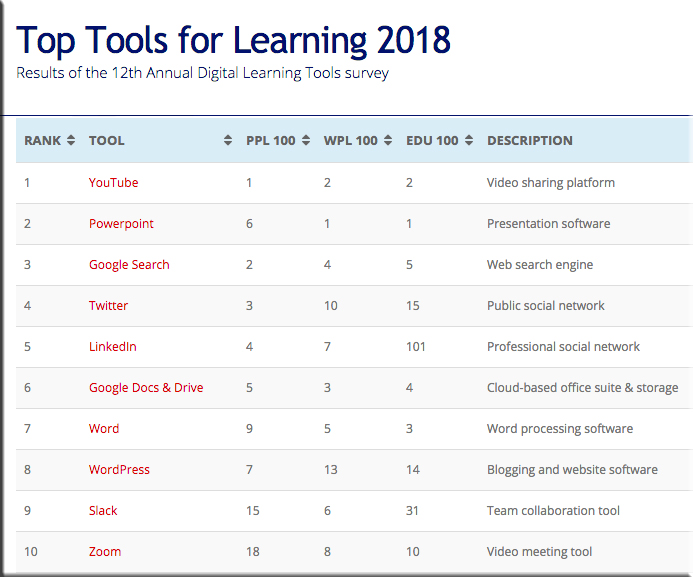

Gen Zers look to teachers first, YouTube second for instruction — from campustechnology.com by Dian Schaffhauser

Excerpt:

Students in Generation Z would rather learn from YouTube videos than from nearly any other form of instruction. YouTube was designated as the preferred mode of learning by 59 percent of Gen Zers in a survey on the topic, compared to in-person group activities with classmates (mentioned by 57 percent), learning applications or games (47 percent) and printed books (also 47 percent). A majority (55 percent) believe that YouTube has “contributed to their education.” In fact, nearly half of survey participants (47 percent) reported spending three or more hours every day on YouTube.

The only method of instruction that beat out YouTube? Teachers. Almost four in five Gen Zers (78 percent) reported that their instructors “are very important to learning and development.” That’s nearly 20 percentage points higher than the YouTube option.

While Millennials also value teachers above all else for learning (chosen by 80 percent), that’s followed by printed books (60 percent), YouTube (55 percent), group activities (47 percent) and apps or games (41 percent).

An example posting:

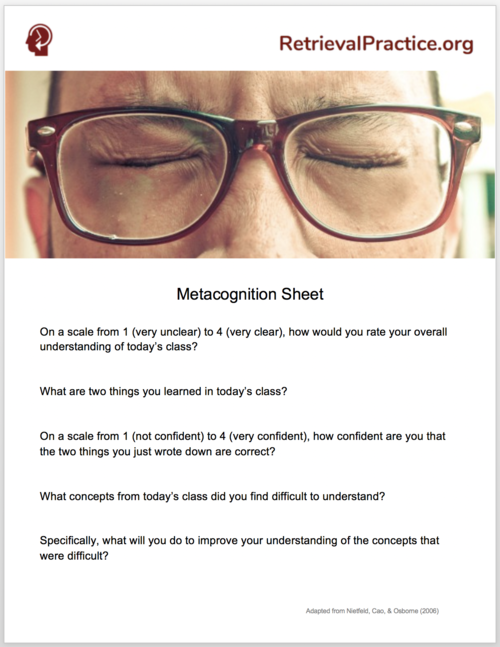

Retrieve, Space, Elaborate, and Transfer with Connection Notebooks — from retrievalpractice.org

Excerpts:

How can we encourage students to retrieve, elaborate, and connect with course content? Here’s a strategy called Connection Notebooks by James M. Lang, Professor at Assumption College. Connection Notebooks include retrieval practice, spacing, elaboration, and transfer – all in five minutes or less!

Ask students to dedicate a specific notebook as their Connection Notebook at the beginning of the semester (or provide one for them) and have them to bring it to class every day. Approximately once a week, ask students to take out their Connection Notebook and write a one-paragraph response to a “connection prompt” at the end of class. For example:

- How does what you learned today connect to something you’ve learned in another class?

- Have you ever encountered something you learned today in a TV show, movie, song, or book?

- Have you ever experienced something you learned today in your life outside of school?

…

Connection Notebooks are effective for a few reasons:

Also, see the work from Learning Scientists | | learningscientists.org

An example posting:

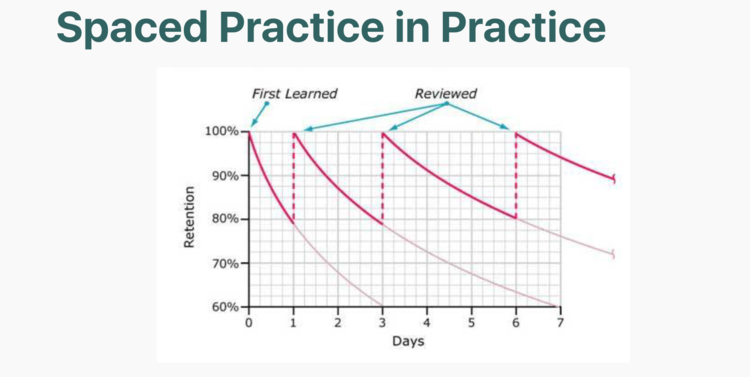

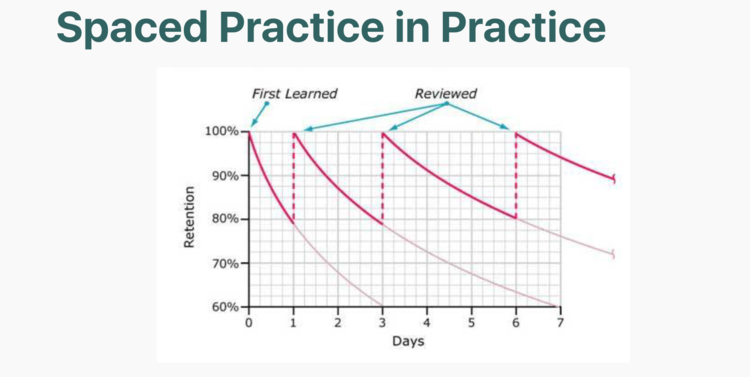

In this digest, we put together 5 blog posts by teachers that focus on implementing spaced practice in one specific subject at a time. For more of an overview of spaced practice, see this guest post by Jonathan Firth (@JW_Firth).