Teaching Financial Literacy — from techlearning.com by Erik Ofgang

More states are adopting financial literacy requirements for students. Here are tips for teaching the topic.

Excerpt:

Teaching students about this financial misinformation is vital, Pelletier says. As is giving students the tools to understand cryptocurrency, NFTs, intense inflation, and student debt, along with more traditional lessons in financial literacy.

Financial Literacy: Teaching and Engagement Resources

There are free online resources with ready-to-go financial lesson plans, videos, and classroom exercises.

While not much time is spent in K-12 educating students about money, once they graduate, it will be an important topic for them. “Not a day will go by that they’re not thinking about money. How to make it, how to spend it, how to save it,” Pelletier says. “And yet it’s like the least thing you’re taught in school.”

From DSC:

I appreciated Erik’s article/topic here and I would add that I wish that we would teach high schoolers about legal-related items such as wills, trusts, power of attorney for health care and for finances, finding legal assistance, etc.

But even as I write this, I recall that my neighbor is leaving our local school district to move to another school district for her kids’ sake (her and her husband’s words, not mine). I get it. Teachers have sooooo much on their plate already. So I don’t mean to throw another item on their jammed-full job plates.

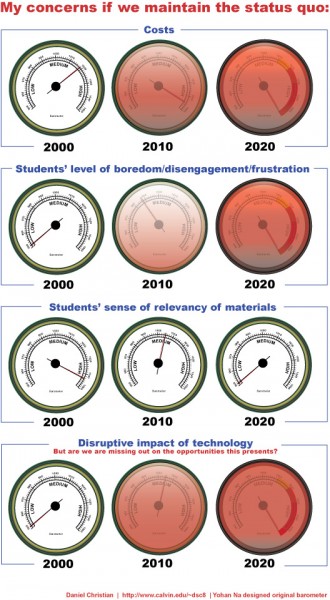

But I hope that we will look at how to redesign our lifelong learning ecosystems to make them even more relevant, helpful, practical, useful, and up-to-date/responsive. We would probably find that the youth would be more attentive if they sensed that the information they are being taught will definitely come in handy in their futures. Better yet, bring former students in via digital video to relay practical examples of things that they — or their parents, grandparents, friends, etc. — are experiencing to the current students.

Also relevant/see:

High School Students Say They Learn The Most Important Skills Outside of School — from edsurge.com by Jeffrey R. Young

Excerpt (emphasis DSC):

The trend that could have a huge impact on education, at the K-12 and college level, Evans argues. For one thing, it’s a challenge to teachers—that they should do more to tap into the intrinsic motivation of students, that students can learn so much more if they’re excited about what they’re doing.

From DSC:

This item from EdSurge mentioned “free agent learning” — so I put a Google Alert out there for this phrase this morning, as I want to learn more about that topic/item.