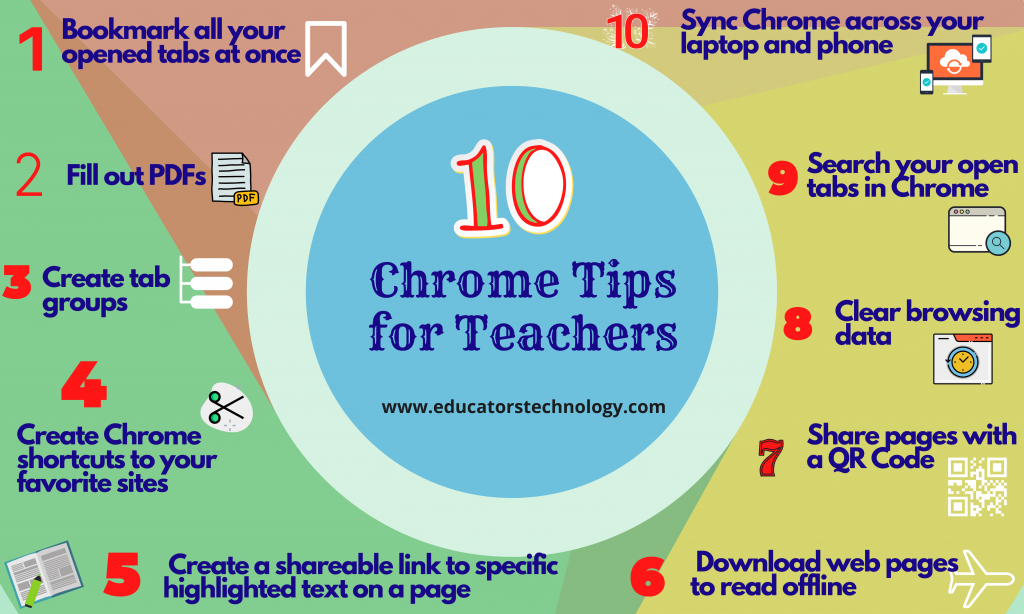

10 great Chrome tips for teachers and educators — from educatorstechnology.com

The Damaging Myth of the Natural Teacher — from chronicle.com by Beth McMurtrie

Excerpt:

The mistaken ideas about teaching that Sathy had early in her career are widespread — and not only among new instructors. Good teaching is often seen as a natural talent when really it’s a skill, one that can be learned and refined.

…

Thinking back to those early days, though, Sathy sees how that first stumble could have led her in a different direction. If it weren’t for a “big lightbulb moment” that enabled her to quickly understand her mistakes, a fierce determination to become a better teacher, and an openness to seeing her role not as the expert who commands a room, but as a partner in students’ learning, she could have been yet another hapless instructor wondering how to get through the semester without too many punishing evaluations.

“I’m glad I had the courage to keep getting back into the ring,” she says.

Five Tips for Launching an Online Writing Group — from scholarlyteacher.com by Kristina Rouech, Betsy VanDeuesen, Holly Hoffman, & Jennifer Majorana — who are all from Central Michigan University

Excerpt:

Making time for writing can be difficult at any stage of your career. Pushing writing aside for grading, lesson planning, meeting with students, and committee work is too easy. However, writing is a necessary part of our careers and has the added benefit of helping us stay current with our practice and knowledge in our field. Lee and Boud (2003) stress that groups should focus on developing peer relationships and writing identity, increasing productivity, and sharing practical writing. Online writing groups can help us accomplish this. With the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, working online has become a necessity, but it can take time to figure out what works best for you and your writing colleagues. We recommend five tips to help you establish an online writing group that is productive and enjoyable for all participants.

Feynman – Don’t lecture and Feynman Technique — from donaldclarkplanb.blogspot.com by Donald Clark

Excerpt from the Feynman Technique section

- Write down everything you think you know about the topic from the top of your head

- Teach it to someone much younger

- Identify the gaps and fill them out

- Simplify, clarify and use analogies

Learning this way is iterative, as you must go back to sources to fill in any gaps uncovered by your attempts to recall what you think you know. The act of writing, teaching, simplification and analogising, is a form of retrieval practice that increases understanding and retention.

Also see:

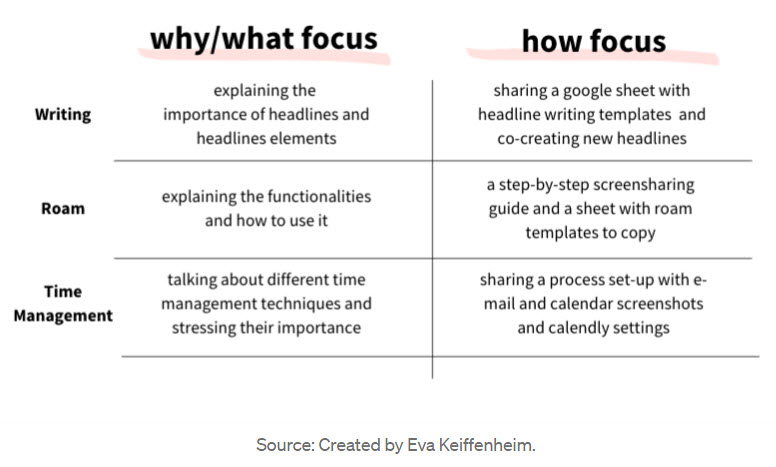

The Feynman Technique Can Help You Remember Everything You Read — from medium.com by Eva Keiffenheim

How to use this simple principle for you.

Excerpts:

Social climber Dale Carnegie used to say knowledge isn’t power until it’s applied. And to apply what you read, you must first remember what you learned.

Nobel Prize-winning physicist Richard Feynman (1918–1988) was an expert for remembering what he learned.

Most people confuse consumption with learning. They think reading, watching, or hearing information will make the information stick with them.

Unless you’ve got a photographic memory, no idea could be further from the truth.

…

Teaching is the most effective way to embed information in your mind. Plus, it’s an easy way to check whether you’ve remembered what you read. Because before you teach, you have to take several steps: filter relevant information, organize this information, and articulate them using your own vocabulary.

The Story is in the Structure: A Multi-Case Study of Instructional Design Teams — from the Online Learning Consortium by Jason Drysdale (other articles here)

Excerpt:

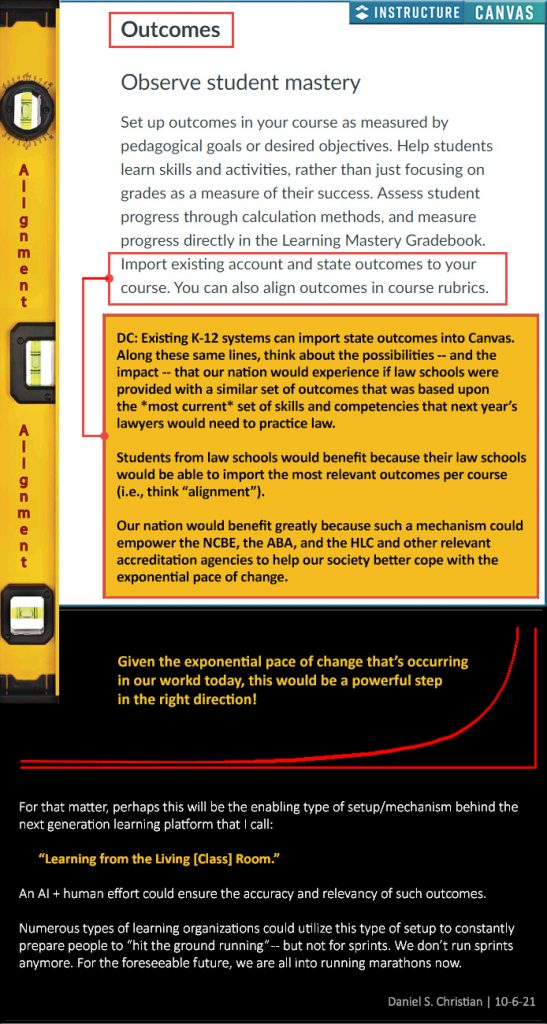

Given the results of this study, it is recommended that institutions that are restructuring or building new instructional design teams implement centralized structures with academic reporting lines for their teams. The benefits of both centralization and academic reporting lines are clear: better advocacy and empowerment, better alignment with the pedagogical work of both designers and faculty, and less role misperception for instructional designers. Structuring these teams toward empowerment and better definitions of their roles as pedagogy experts may help them sustain their leadership on the initiatives they led, to great effect, during the COVID-19 pandemic. This study also revealed the importance of three additional structural elements: appropriate instructional design staffing for the size and scale of the institution, leadership experience with instructional design, and positional parity with faculty.

Also see:

- A Practitioner’s Guide to Instructional Design in Higher Education — from by Jill E. Stefaniak, Sheri Conklin, Beth Oyarzun, & Rebecca M. Reese