Chapter 2 of the Daniel Willingham’s book entitled, Why Don’t Students Like School: A Cognitive Scientist Answers Questions About How the Mind Works and What It Means for the Classroom, lays out the best case for the liberal arts degree that I’ve ever seen or read about.

First of all, a description of the book:

Easy-to-apply, scientifically-based approaches for engaging students in the classroom

Cognitive scientist Dan Willingham focuses his acclaimed research on the biological and cognitive basis of learning. His book will help teachers improve their practice by explaining how they and their students think and learn. It reveals-the importance of story, emotion, memory, context, and routine in building knowledge and creating lasting learning experiences.

- Nine, easy-to-understand principles with clear applications for the classroom

- Includes surprising findings, such as that intelligence is malleable, and that you cannot develop “thinking skills” without facts

- How an understanding of the brain’s workings can help teachers hone their teaching skills

From DSC:

Though more tangential to my main point here, I really appreciate Daniel’s bridging the worlds of research and teaching. He is knowledgeable about the relevant research that’s been done out there, and he uses that knowledge to inform his recommendations for how best to apply that research in the classroom. Often, it seems, these two worlds don’t get connected. I also like how he models solid ways of teaching. For example, he knows that repetition helps, so he summarizes/repeats his main points throughout a chapter.

Speaking of chapters, here are some of my notes from chapter 2:

- Factual knowledge must proceed skill. (p. 25)

- We need factual knowledge before we can practice critical thinking or have the ability to analyze something (p. 25)

- “Thinking well requires knowing facts, and that’s true not simply because you need something to think about. The very processes that teachers care about most — critical thinking processes such as reasoning and problem solving – are intimately intertwined with factual knowledge that is stored in long-term memory…” (p. 28)

- Critical thinking processes are tied to background knowledge (p. 29)

- Thinking skills and knowledge are bound together (p.29)

- “The phenomenon of tying together separate pieces of information from the environment is called chunking. The advantage is obvious: you can keep more stuff in working memory if it can be chunked. The trick, however, is that chunking works only when you have applicable factual knowledge in long-term memory.” (p. 34)

- “Thus, background knowledge allows chunking, which makes more room in working memory, which makes it easier to relate ideas, and therefore to comprehend.” (p.35)

- “…we don’t take in new information in a vacuum. We interpret new things we read in light of other information we already have on the topic.” (p. 36)

- “Not only does background knowledge make you a better reader, but it also is necessary to be a good thinker.” (p.37)

- “When it comes to knowledge, those who have more gain more.” (p. 42)

- “When it comes to knowledge, the rich get richer. (p.45 )

- “…having background knowledge in long-term memory makes it easier to acquire still more factual knowledge.” (p. 44)

- “Knowledge…is a prerequisite for imagination.” (p.46)

- “The cognitive processes that are most esteemed — logical thinking, problem solving, and the like — are intertwined with knowledge.” (pgs. 46-47)

From DSC:

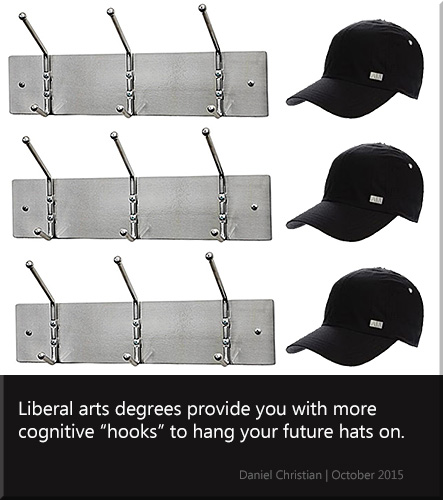

So the saying that “you get what you pay for” again turns out to be true. That is, you will likely pay more for a 4-year liberal arts degree than what you will pay for a 10-12 week bootcamp. But if you go to a bootcamp and come out knowing only how to code using programming language XYZ, you have far fewer cognitive “hooks” on which to hang new hats (i.e., new information).

A liberal arts degree covers and provides a great deal of knowledge — and it builds upon that knowledge with higher order skills. Such a degree provides a broader foundation of knowledge that creates numerous hooks on which to hang new hats in the future.

These reflections regarding foundational knowledge and having hooks to hang new information on (and make new connections with) reminds me of Bloom’s Taxonomy. Factual knowledge was the foundational layer of his original taxonomy:

Original

Revised

So it seems to me that the size/breadth of the foundational layer that’s been built from a liberal arts degree is far broader and deeper than a foundational layer obtained from attending a bootcamp. The numerous number of cognitive hooks that it provides will help a sharp, hard-working graduate of a liberal arts program be able to not only understand the business at hand, but to practice creative thinking, to practice critical thinking, and to be able to innovate.

I’m not saying that a graduate of a bootcamp can’t do some of those things as well. (I also think that bootcamps can definitely have a place in our learning ecosystems.) But chances are that such a person has already built a broader foundation of remembering and understanding to draw upon.

What do you think, am I off base here or does this thinking accurately reflect

one of the areas in which a liberal arts degree is important and provides real, lasting value?