Summary of the #LrnSciChat on 19 February 2019 on

Dual Coding in Learning and Teaching. — from wakelet.com

Dual coding is simply combining verbal and visual information to enrich the learning experience.

Dr. C. Kuepper-Tetzel

Also see the posters out at The Learning Scientists website.

From DSC:

From Mary Grush’s recent article re: Learning Engineering, I learned that back in the late 1960’s, Herbert Simon believed there would be value in providing college presidents with “learning engineers” (see his article entitled, “The Job of a College President”).

An excerpt:

What do we find in a university? Physicists well educated in physics, and trained for research in that discipline; English professors learned in their language and its literature (or at least some tiny corner of it); and so on down the list of the disciplines. But we find no one with a professional knowledge of the laws of learning, or of the techniques for applying them (unless it be a professor of educational psychology, who teaches these laws, but has no broader responsibility for their application in the college).

Notice, our topic is learning, not teaching. A college is a place where people come to learn. How much or how little teaching goes on there depends on whether teaching facilitates learning, and if so, under what circumstances. It is a measure of our naivete that we assume implicitly, in almost all our practices, that teaching is the way to produce learning, and that something called a “class” is the best environment for teaching.

But what do we really know about the learning process: about how people learn, about what they learn, and about what they can do with what they learn? We know a great deal today, if by “we” is meant a relatively small group of educational psychologists who have made this their major professional concern. We know much less, if by “we” is meant the rank and file of college teachers.

What is learned must be defined in terms of what the student should be able to do. If learning means change in the student, then that change should be visible in changed potentialities of behavior.

Herbert Simon, 1967

From DSC:

You will find a great deal of support for active learning in Simon’s article.

Philippians 4:9 New International Version (NIV) — biblegateway.com

9 Whatever you have learned or received or heard from me, or seen in me—put it into practice. And the God of peace will be with you.

James 1:22-25 New International Version (NIV) — from biblegateway.com

22 Do not merely listen to the word, and so deceive yourselves. Do what it says.23 Anyone who listens to the word but does not do what it says is like someone who looks at his face in a mirror 24 and, after looking at himself, goes away and immediately forgets what he looks like. 25 But whoever looks intently into the perfect law that gives freedom, and continues in it—not forgetting what they have heard, but doing it—they will be blessed in what they do.

From DSC:

The word engagement comes to mind here…as does the association between doing and not forgetting (i.e., memory…recall…creating “mental hooks” to hang future learning/content on…which can ultimately impact our behaviors).

The Lesson You Never Got Taught in School: How to Learn! — from bigthink.com by Simon Oxenham (from 2/15/13)

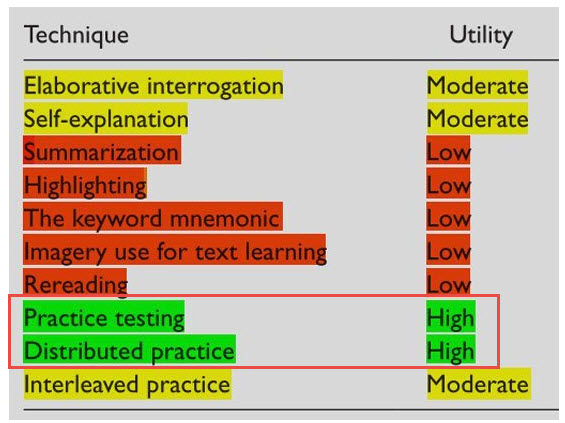

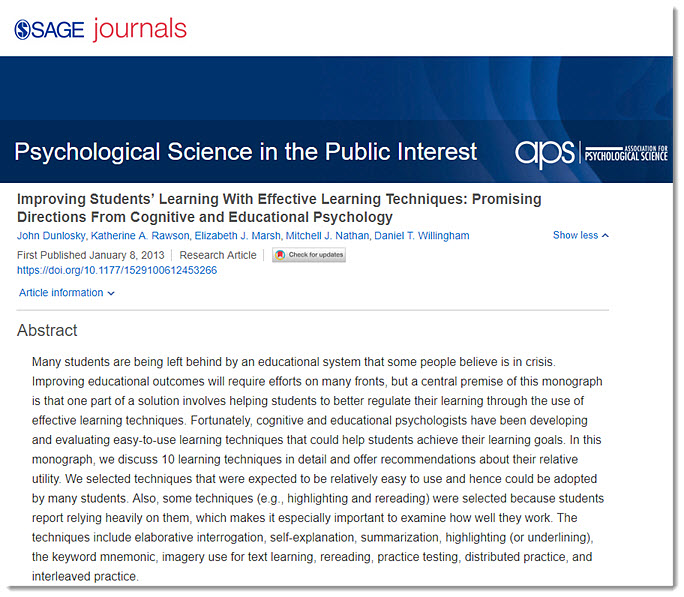

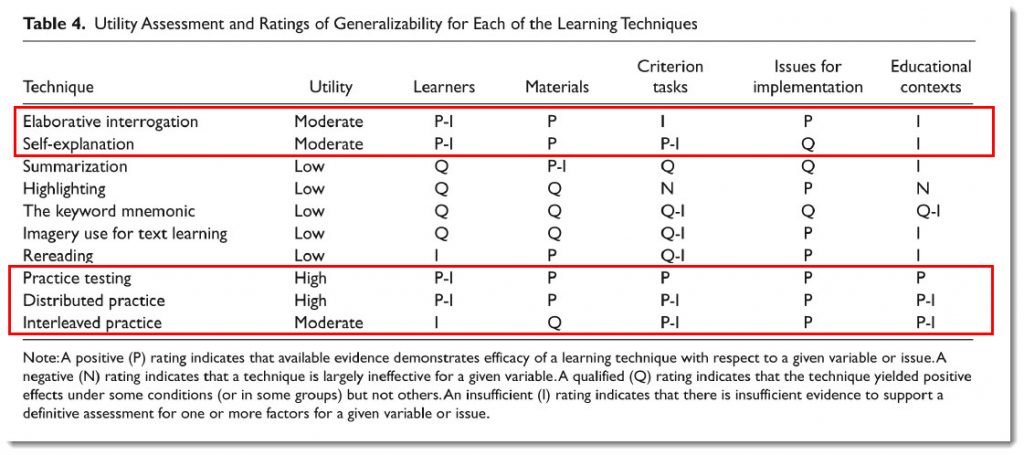

Psychological Science in the Public Interest evaluated ten techniques for improving learning, ranging from mnemonics to highlighting and came to some surprising conclusions.

Excerpts:

Practice Testing (Rating = High)

This is where things get interesting; testing is often seen as a necessary evil of education. Traditionally, testing consists of rare but massively important ‘high stakes’ assessments. There is however, an extensive literature demonstrating the benefits of testing for learning – but importantly, it does not seem necessary that testing is in the format of ‘high stakes’ assessments. All testing including ‘low stakes’ practice testing seems to result in benefits. Unlike many of the other techniques mentioned, the benefits of practice testing are not modest – studies have found that a practice test can double free recall!

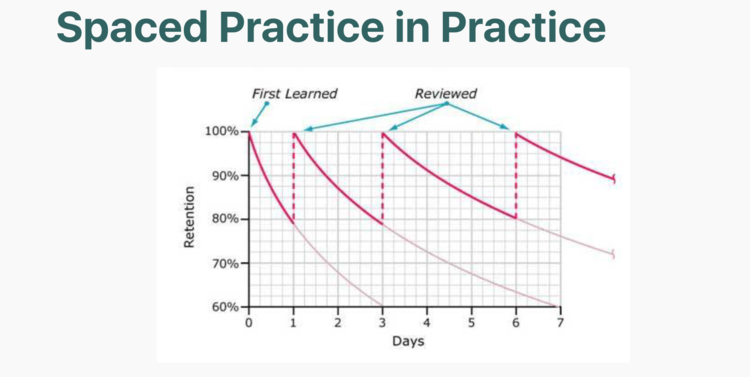

Distributed Practice (Rating = High)

Have you ever wondered whether it is best to do your studying in large chunks or divide your studying over a period of time? Research has found that the optimal level of distribution of sessions for learning is 10-20% of the length of time that something needs to be remembered. So if you want to remember something for a year you should study at least every month, if you want to remember something for five years you should space your learning every six to twelve months. If you want to remember something for a week you should space your learning 12-24 hours apart. It does seem however that the distributed-practice effect may work best when processing information deeply – so for best results you might want to try a distributed practice and self-testing combo.

Also see:

- Improving Students’ Learning With Effective Learning Techniques: Promising Directions From Cognitive and Educational Psychology

John Dunlosky, Katherine A. Rawson, Elizabeth J. Marsh, Mitchell J. Nathan, Daniel T. Willingham

First Published January 8, 2013 | Research Article

https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100612453266

- Study smart — from apa.org by Lea Winerman; as recommended by Daniel Willingham here

Make the most of your study time with these drawn-from-the-research tips.

Per Willingham (emphasis DSC):

- Rereading is a terribly ineffective strategy. The best strategy–by far — is to self-test — which is the 9th most popular strategy out of 11 in this study. Self-testing leads to better memory even compared to concept mapping (Karpicke & Blunt, 2011).

Three Takeaways from Becoming An Effective Learner:

- Boser says that the idea that people have different learning styles, such as visual learning or verbal learning, has little scientific evidence to support it.

- According to Boser, teachers and parents should praise their kids’ ability and effort, instead of telling them they’re smart. “When we tell people they are smart, we give them… a ‘fixed mindset,’” says Boser.

- If you are learning piano – or anything, really – the best way to learn is to practice different composers’ work. “Mixing up your practices is far more effective,” says Boser.

Cumulative exams aren’t the same as spacing and interleaving. Here’s why. — from retrievalpractice.org

Excerpts (emphasis DSC):

Our recommendations to make cumulative exams more powerful with small tweaks for you and your students:

- Cumulative exams are good, but encourage even more spacing and discourage cramming with cumulative mini-quizzes throughout the semester, not just as an end-of-semester exam.

- Be sure that cumulative mini-quizzes, activities, and exams include similar concepts that require careful discrimination from students, not simply related topics.

- Make sure you are using spacing and interleaving as learning strategies and instructional strategies throughout the semester, not simply as part of assessments and cumulative exams.

Bottom line: Just because an exam is cumulative does not mean it automatically involves spacing or interleaving. Be mindful of relationships across exam content, as well as whether students are spacing their study throughout the semester or simply cramming before an exam – cumulative or otherwise.

From DSC:

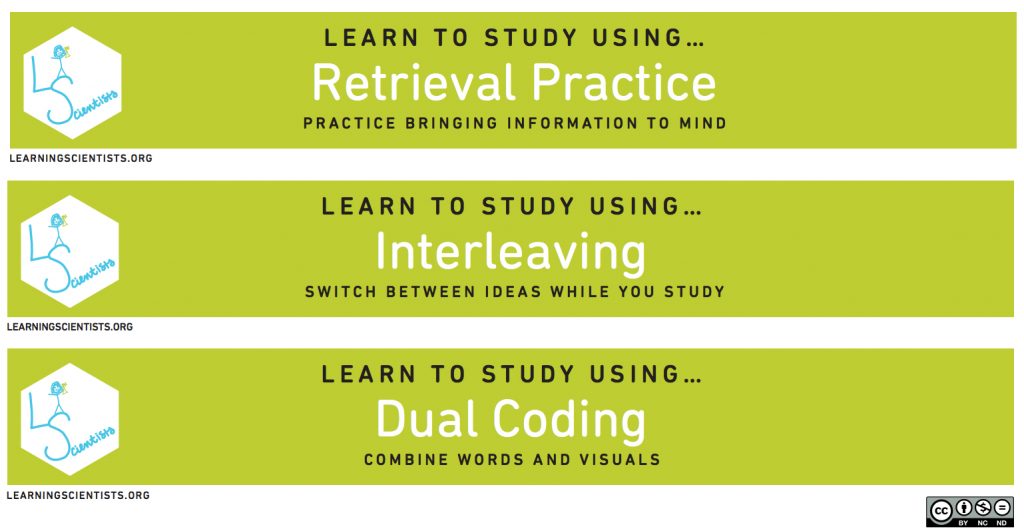

We, like The Learning Scientists encourages us to do and even provides their own posters, should have posters with these tips on them throughout every single school and library in the country. The posters each have a different practice such as:

- Spaced practice

- Retrieval practice

- Elaboration

- Interleaving

- Concrete examples

- Dual coding

That said, I could see how all of that information could/would be overwhelming to some students and/or the more technical terms could bore them or fly over their heads. So perhaps we could boil down the information to feature excerpts from the top sections only that put the concepts into easier to digest words such as:

- Practice bringing information to mind

- Switch between ideas while you study

- Combine words and visuals

- Etc.

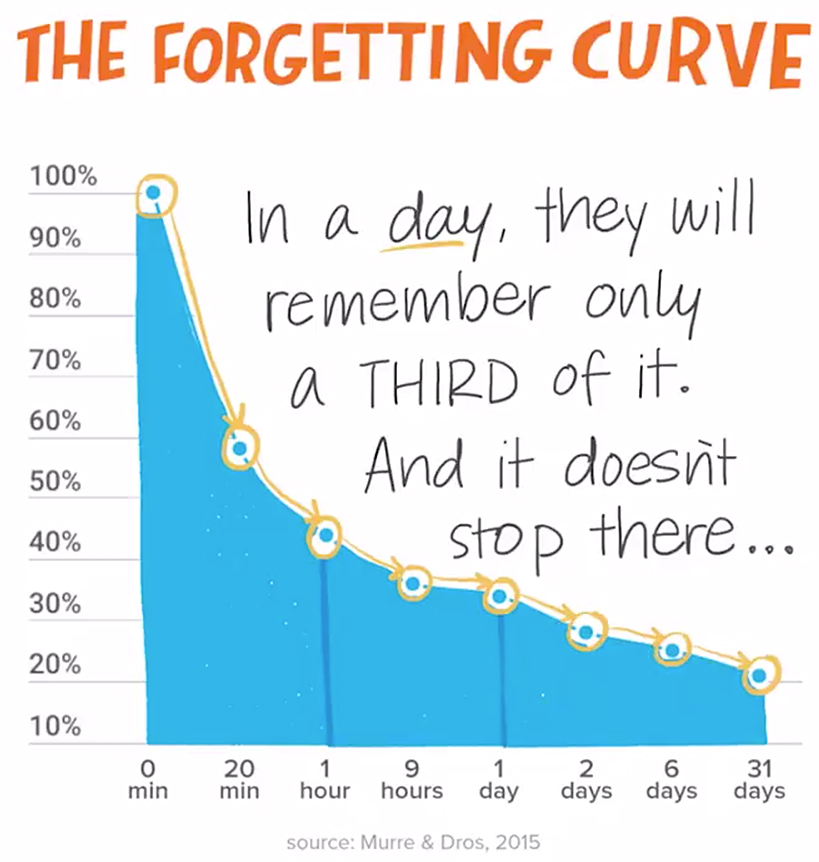

Humans are hardwired to forget. But research shows that strategies like peer-to-peer explanations, regular review, and interleaving can boost retention. pic.twitter.com/0IVVz2M3FJ

— edutopia (@edutopia) December 6, 2018

From DSC:

This is where the quizzing features/tools within a Learning Management System such as Canvas, Moodle, Blackboard Learn, etc. are so valuable. They provide students with opportunities for low-stakes (or no-stakes) practice in retrieving information and to see if they are understanding things or not. Doing such formative assessments along the way can point out areas where they need further practice, as well as areas where the students are understanding things well (and only need an occasional question or two on that item in order to reduce the effects of the forgetting curve).

Combining retrieval, spacing, and feedback boosts STEM learning — from retrievalpractice.org

Punchline:

Scientists demonstrated that when college students used a quizzing program that combined retrieval practice, spacing, and feedback, exam performance increased by nearly a letter grade.

—-

Abstract

The most effective educational interventions often face significant barriers to widespread implementation because they are highly specific, resource intense, and/or comprehensive. We argue for an alternative approach to improving education: leveraging technology and cognitive science to develop interventions that generalize, scale, and can be easily implemented within any curriculum. In a classroom experiment, we investigated whether three simple, but powerful principles from cognitive science could be combined to improve learning. Although implementation of these principles only required a few small changes to standard practice in a college engineering course, it significantly increased student performance on exams. Our findings highlight the potential for developing inexpensive, yet effective educational interventions that can be implemented worldwide.

…

In summary, the combination of spaced retrieval practice and required feedback viewing had a powerful effect on student learning of complex engineering material. Of course, the principles from cognitive science could have been applied without the use of technology. However, our belief is that advances in technology and ideas from machine learning have the potential to exponentially increase the effectiveness and impact of these principles. Automation is an important benefit, but technology also can provide a personalized learning experience for a rapidly growing, diverse body of students who have different knowledge and academic backgrounds. Through the use of data mining, algorithms, and experimentation, technology can help us understand how best to implement these principles for individual learners while also producing new discoveries about how people learn. Finally, technology facilitates access. Even if an intervention has a small effect size, it can still have a substantial impact if broadly implemented. For example, aspirin has a small effect on preventing heart attacks and strokes when taken regularly, but its impact is large because it is cheap and widely available. The synergy of cognitive science, machine learning, and technology has the potential to produce inexpensive, but powerful learning tools that generalize, scale, and can be easily implemented worldwide.

Keywords: Education. Technology. Retrieval practice. Spacing. Feedback. Transfer of learning.

Awesome study hacks: 5 ways to remember more of what you read — from academiccoachingwithpat.com by Pat LaDouceur; with thanks to Julia Reed for her Tweet on this

Excerpts:

- Annotate as you read

- Skim

- Rewrite key ideas in your own words

- Write a critique

- List your questions

Reorganizing information helps you learn it more effectively, which is why Rewriting makes the list as one of the top 5 reading study hacks. It forces you to stay active and involved with the text (from DSC: the word “engaged” comes to mind here), to consider arguments and synthesize information, and thus remember more of what you read.

From DSC:

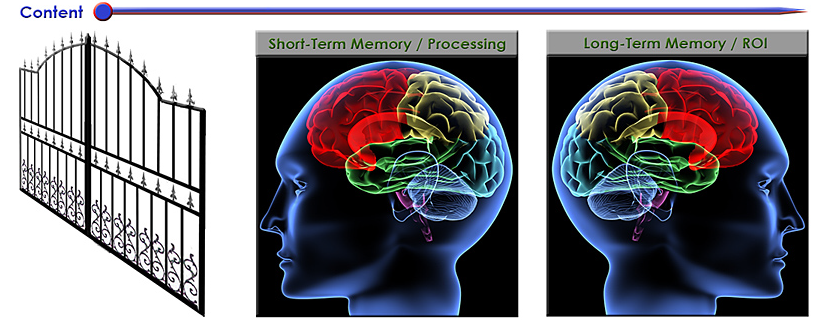

Ever notice how effective Ted Talks begin? They seek to instantly grab your attention with a zinger question, a somewhat shocking statement, an interesting story, a joke, an important problem or an issue, a personal anecdote or experience, a powerful image/photo/graphic, a brief demonstration, and the like.

Grabbing someone’s attention is a key first step in getting a piece of information into someone’s short-term memory — what I call getting through “the gate.” If we can’t get through the gate into someone’s short-term memory, we have zero (0) chance of having them actually process that information and to think about and engage with that piece of content. If we can’t make it into someone’s short-term memory, we can’t get that piece of information into their long-term memory for later retrieval/recall. There won’t be any return on investment (ROI) in that case.

So why not try starting up one of your classes this week with a zinger question, a powerful image/photo/video, or a story from your own work experience? I’ll bet you’ll grab your students’ attentions instantly! Then you can move on into the material for a greater ROI. From there, offering frequent, low-stakes quizzes will hopefully help your students slow down their forgetting curves and help them practice recalling/retrieving that information. By the way, that’s why stories are quite powerful. We often remember them better. So if you can weave an illustrative story into your next class, your students might really benefit from it come final test time!

Also relevant/see:

Ready, set, speak: 5 strong ways to start your next presentation — from abovethelaw.com by Olga Mack, with thanks to Mr. Otto Stockmeyer for this resource

No matter which of these five ways you decide to launch your presentation, ensure that you make it count, and make it memorable.

Excerpts:

- Tell a captivating story

- Ask thought-provoking questions to the audience

- State a shocking headline or statistic

- Use a powerful quote

- Use silence

When delivering a speech, a pause of about three or even as many as 10 seconds will allow your audience to sit and quiet down. Because most people always expect the speaker to start immediately, this silence will thus catch the attention of the audience. They will be instinctively more interested in what you had to say, and why you took your time to say it. This time will also help you gather your nerves and prepare to speak.

Why giving kids a roadmap to their brain can make learning easier — from edsurge.com by Megan Nellis

Excerpts:

Learning, Down to a Science

Metacognition. Neuroplasticity. Retrieval Practice. Amygdala. These aren’t the normal words you’d expect to hear in a 15-year-old rural South African’s vocabulary. Here, though, it’s common talk. And why shouldn’t it be? Over the years, we’ve found youth are innately hungry to learn about the inner workings of their mind—where, why and how learning, thinking and decision-making happens. So, we teach them cognitive science.

…

Over the next three years, we teach students about the software and hardware of the brain. From Carol Dweck’s online Brainology curriculum, they learn about growth mindset, memory and mnemonics, the neural infrastructure of the brain. They learn how stress impacts learning and about neuroplasticity—or how the brain learns. From David Eagleman and Dan Siegel, they learn about the changing landscape of the adolescent brain and how novelty, emotionality and peer relationships aid in learning.

…

Pulling from books such as Make It Stick and How We Learn, we pointedly teach students about the science behind retrieval practice, metacognition and other strategies. We expressly use them in our classes so students see and experience the direct impact, and we also dedicate a whole class in our program for students to practice applying these strategies toward their own academic learning from school.

From DSC to teachers and professors:

Should these posters be in your classroom? The posters each have a different practice such as:

- Spaced practice

- Retrieval practice

- Elaboration

- Interleaving

- Concrete examples

- Dual coding

That said, I could see how all of that information could/would be overwhelming to some students and/or the more technical terms could bore them or fly over their heads. So perhaps you could boil down the information to feature excerpts from the top sections only that put the concepts into easier to digest words such as:

- Practice bringing information to mind

- Switch between ideas while you study

- Combine words and visuals

- Etc.

Why demand originality from students in online discussion forums? — from facultyfocus.com by Ronald Jones

Excerpt:

Tell me in your own words

Why demand originality? In relating to a traditional classroom discussion, do students respond to the professor’s question by opening up the textbook or searching for the answer on the Internet and then reading off the answer? Some might try, but by asking questions the professor is looking to see if the students grasp the discussed concept, not if they know how and where to find the answer.

Online students have the advantage of reflection time, along with having the textbook and Internet search engine open when responding to discussion questions. With a few simple clicks, virtually any question can be answered by searching the Internet. Once again, why demand originality? Classroom learning takes place when students are required to think; that’s a few steps beyond clicking copy and paste. As instructors, we should encourage our students to be resourceful and to learn the skills of locating and incorporating scholarly literature into their work. But we also must instill the learning value of synthesizing sources in such a manner that produces evidence of gained knowledge.

From DSC:

I like the idea of asking students to put it into their own words. Not just to get by the issue of copying/pasting or trying to stem plagiarism, but because it’s more along the line of journaling about our learning. We need to actually engage with some content in order to put that content into our own words. Not outsourcing our learning to others. Journaling can help us clarify what we’re understanding and where we still have questions and/or concerns.

Encouraging participation of all in the course: Moving from intact classes to individuals students — from scholarlyteacher.com by Todd Zakrajsek, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill

Excerpts:

During every class session, read the room by watching individuals. Are students taking notes, nodding along as others speak, or even advancing the discussion by building on the comments of classmates? Are verbal responses merely defining terminology, or do they make connections between the text and real-world examples? Analyze the extent to which certain examples or content areas are received by individual students. Take note when student responses are merely noise to fill the void when you are not talking. Overall, look for individual characteristics that emerge within your course as a community of learning is being established.

…

Keep in mind that it is often less threatening to one’s ego to claim a lack of preparation for class than it is to admit that one is finding it difficult to understand the material. For those who need a bit of motivation to come prepared, a quiz at the beginning of class will help students to come to class ready to discuss the material for that day.

…

As all students are pressed for time these days, a quiz might be the added motivation that most students need. These quizzes do not need to be extremely challenging, but they should be challenging enough to ensure the required preparation is done. That is, one should not be able to get responses correct simply by guessing. For students who do not understand the material, quizzes will not prepare them to engage in class discussions or to answer your questions during a discussion lecture. For those students, failed quizzes might add additional pressure and cause less engagement with the material. Struggling students who are not prepared for class need assistance to understand the material. Carefully structured small group projects and discussions might be the best way to get their voices into the class. Ask increasingly difficult questions as part of the discussion, and when you know you have struggling students reserve some of the easier questions for those students.

Gen Zers look to teachers first, YouTube second for instruction — from campustechnology.com by Dian Schaffhauser

Excerpt:

Students in Generation Z would rather learn from YouTube videos than from nearly any other form of instruction. YouTube was designated as the preferred mode of learning by 59 percent of Gen Zers in a survey on the topic, compared to in-person group activities with classmates (mentioned by 57 percent), learning applications or games (47 percent) and printed books (also 47 percent). A majority (55 percent) believe that YouTube has “contributed to their education.” In fact, nearly half of survey participants (47 percent) reported spending three or more hours every day on YouTube.

The only method of instruction that beat out YouTube? Teachers. Almost four in five Gen Zers (78 percent) reported that their instructors “are very important to learning and development.” That’s nearly 20 percentage points higher than the YouTube option.

While Millennials also value teachers above all else for learning (chosen by 80 percent), that’s followed by printed books (60 percent), YouTube (55 percent), group activities (47 percent) and apps or games (41 percent).

Also, see the work from Pooja K. Agarwal | @PoojaAgarwal

Assistant Professor, Cognitive Scientist, & Former K-12 Teacher. Follow @RetrieveLearn and subscribe for teaching strategies at http://retrievalpractice.org.

An example posting:

Retrieve, Space, Elaborate, and Transfer with Connection Notebooks — from retrievalpractice.org

Excerpts:

How can we encourage students to retrieve, elaborate, and connect with course content? Here’s a strategy called Connection Notebooks by James M. Lang, Professor at Assumption College. Connection Notebooks include retrieval practice, spacing, elaboration, and transfer – all in five minutes or less!

Ask students to dedicate a specific notebook as their Connection Notebook at the beginning of the semester (or provide one for them) and have them to bring it to class every day. Approximately once a week, ask students to take out their Connection Notebook and write a one-paragraph response to a “connection prompt” at the end of class. For example:

- How does what you learned today connect to something you’ve learned in another class?

- Have you ever encountered something you learned today in a TV show, movie, song, or book?

- Have you ever experienced something you learned today in your life outside of school?

…

Connection Notebooks are effective for a few reasons:

- Students build connections over time and across diverse contexts

- Students engage in retrieval practice, spacing, elaboration, and transfer

- Students focus on learning, not assessment, by keeping it low-stakes

Also, see the work from Learning Scientists | @AceThatTest | learningscientists.org

An example posting:

In this digest, we put together 5 blog posts by teachers that focus on implementing spaced practice in one specific subject at a time. For more of an overview of spaced practice, see this guest post by Jonathan Firth (@JW_Firth).

You’re already harnessing the science of learning (you just don’t know it) — from edsurge.com by Pooja Agarwal

Excerpt (emphasis DSC):

Now, a decade later, I see the same clicker-like trend: tools like Kahoot, Quizlet, Quizizz and Plickers are wildly popular due to the increased student engagement and motivation they can provide. Meanwhile, these tech tools continue to incorporate powerful strategies for learning, which are discussed less often. Consider, for example, four of the most robust research-based strategies from the science of learning:

- Retrieval practice

- Spaced practice

- Interleaving

- Feedback

Sound familiar? It’s because approaches that encourage students to use what they know, revisit it over time, mix it up and learn about their own learning are core elements in many current edtech tools. Kahoot and Quizlet, for example, provide numerous retrieval formats, reminders, shuffle options and instant feedback. A century of scientific researchdemonstrates that these features don’t simply increase engagement—they also improve learning, higher order thinking and transfer of knowledge.

From DSC:

Pastors should ask this type of question as well: “What did we talk about the last time we met?” — then give the congregation a minute to write down what they can remember.

Also from Pooja Agarwal and RetrievalPractice.org

For teachers, here’s what we share in a minute or less about retrieval practice:

- Retrieval practice can raise students’ grades from a C to an A, with a significant benefit even after an entire school year

- Retrieval practice boosts learning for a wide variety of ages, subject areas, and settings

- It doesn’t take more time! No extra prep, class, or grading time

And when it comes to students, the first thing we share are Retrieval Warm Ups. These quick, fun questions engage students in class discussion and start a conversation about how retrieval is something we do every day. Try one of these with a teacher to start a conversation about retrieval practice, too!

Cake, cake, cake. That’s the theme for today’s update! — from Pooja Agarwal and retrievalpractice.org

In addition to loving cake, this sweet delight illustrates how we can best support learning in the classroom: with retrieval practice, formative assessment, and summative assessment.

Read on for yummy goodness:

- How these three ingredients are similar and different

- Why this combination makes for a perfect cake

- Why learning is not a bake off, cupcake war, or throw down (sorry to disappoint!)

Three key ingredients for learning

Chances are, you’re familiar with this two-part process:

Formative assessment: Checking on and monitoring students’ learning, which provides teachers and students with information about progress. We think of formative assessment as inserting a toothpick to see how the cake is doing while it’s baking.

Summative assessment: Discovering what students know by measuring learning. This is when we get to celebrate accomplishments with cake and also get a sense of what can be improved upon.

But where does retrieval practice fit in?

Retrieval practice: Learning how to crack an egg, measure ingredients, and mix it all together. This is when we embrace mistakes rather than emphasize perfection, because challenges are a good thing for learning.

What does this mean for you?

Key similarity: All three involve bringing information to mind. In other words, they all require retrieval! From the outside, it can look like one seamless process, and that’s a good thing. Learning isn’t linear and neither is retrieval.

Key difference: Retrieval practice doesn’t require data collection. Nothing needs to be recorded in the gradebook. Retrieval is a no-stakes opportunity when students can experiment, be challenged, and improve over time.

Takeaway: For powerful learning, we must be mindful of which ingredients we’re using, which stage we’re in, and how we can incorporate even more retrieval practice throughout the entire learning (and baking) process.

Also, be sure to see their guides here: