It’s so important the reason we teach! It’s not just about filling their heads for the test! pic.twitter.com/kaPhWwjHET

— carl jarvis (@carljarvis_eos) November 22, 2015

Chapter 2 of the Daniel Willingham’s book entitled, Why Don’t Students Like School: A Cognitive Scientist Answers Questions About How the Mind Works and What It Means for the Classroom, lays out the best case for the liberal arts degree that I’ve ever seen or read about.

First of all, a description of the book:

Easy-to-apply, scientifically-based approaches for engaging students in the classroom

Cognitive scientist Dan Willingham focuses his acclaimed research on the biological and cognitive basis of learning. His book will help teachers improve their practice by explaining how they and their students think and learn. It reveals-the importance of story, emotion, memory, context, and routine in building knowledge and creating lasting learning experiences.

- Nine, easy-to-understand principles with clear applications for the classroom

- Includes surprising findings, such as that intelligence is malleable, and that you cannot develop “thinking skills” without facts

- How an understanding of the brain’s workings can help teachers hone their teaching skills

From DSC:

Though more tangential to my main point here, I really appreciate Daniel’s bridging the worlds of research and teaching. He is knowledgeable about the relevant research that’s been done out there, and he uses that knowledge to inform his recommendations for how best to apply that research in the classroom. Often, it seems, these two worlds don’t get connected. I also like how he models solid ways of teaching. For example, he knows that repetition helps, so he summarizes/repeats his main points throughout a chapter.

Speaking of chapters, here are some of my notes from chapter 2:

- Factual knowledge must proceed skill. (p. 25)

- We need factual knowledge before we can practice critical thinking or have the ability to analyze something (p. 25)

- “Thinking well requires knowing facts, and that’s true not simply because you need something to think about. The very processes that teachers care about most — critical thinking processes such as reasoning and problem solving – are intimately intertwined with factual knowledge that is stored in long-term memory…” (p. 28)

- Critical thinking processes are tied to background knowledge (p. 29)

- Thinking skills and knowledge are bound together (p.29)

- “The phenomenon of tying together separate pieces of information from the environment is called chunking. The advantage is obvious: you can keep more stuff in working memory if it can be chunked. The trick, however, is that chunking works only when you have applicable factual knowledge in long-term memory.” (p. 34)

- “Thus, background knowledge allows chunking, which makes more room in working memory, which makes it easier to relate ideas, and therefore to comprehend.” (p.35)

- “…we don’t take in new information in a vacuum. We interpret new things we read in light of other information we already have on the topic.” (p. 36)

- “Not only does background knowledge make you a better reader, but it also is necessary to be a good thinker.” (p.37)

- “When it comes to knowledge, those who have more gain more.” (p. 42)

- “When it comes to knowledge, the rich get richer. (p.45 )

- “…having background knowledge in long-term memory makes it easier to acquire still more factual knowledge.” (p. 44)

- “Knowledge…is a prerequisite for imagination.” (p.46)

- “The cognitive processes that are most esteemed — logical thinking, problem solving, and the like — are intertwined with knowledge.” (pgs. 46-47)

From DSC:

So the saying that “you get what you pay for” again turns out to be true. That is, you will likely pay more for a 4-year liberal arts degree than what you will pay for a 10-12 week bootcamp. But if you go to a bootcamp and come out knowing only how to code using programming language XYZ, you have far fewer cognitive “hooks” on which to hang new hats (i.e., new information).

A liberal arts degree covers and provides a great deal of knowledge — and it builds upon that knowledge with higher order skills. Such a degree provides a broader foundation of knowledge that creates numerous hooks on which to hang new hats in the future.

These reflections regarding foundational knowledge and having hooks to hang new information on (and make new connections with) reminds me of Bloom’s Taxonomy. Factual knowledge was the foundational layer of his original taxonomy:

Original

Revised

So it seems to me that the size/breadth of the foundational layer that’s been built from a liberal arts degree is far broader and deeper than a foundational layer obtained from attending a bootcamp. The numerous number of cognitive hooks that it provides will help a sharp, hard-working graduate of a liberal arts program be able to not only understand the business at hand, but to practice creative thinking, to practice critical thinking, and to be able to innovate.

I’m not saying that a graduate of a bootcamp can’t do some of those things as well. (I also think that bootcamps can definitely have a place in our learning ecosystems.) But chances are that such a person has already built a broader foundation of remembering and understanding to draw upon.

What do you think, am I off base here or does this thinking accurately reflect

one of the areas in which a liberal arts degree is important and provides real, lasting value?

Every learner is different but not because of their learning styles — from clive-shepherd.blogspot.com by Clive Sheperd

Excerpt:

I’ve been reading Make it Stick: The Science of Successful Learning by Peter Brown and Henry Roediger (Harvard University Press, 2014). What a great book! It provides a whole load of useful tips for learners, teachers and trainers based on solid research.

…

Finishing this book coincides with The Debunker Club’s Debunk Learning Styles Month. And learning styles really do need debunking, not because we, as learners, don’t have preferences, but because there is no model out there which has been proven to be genuinely helpful in predicting learner performance based on their preferences.

Learning Styles are NOT an Effective Guide for Learning Design — from debunker.club

Excerpt:

Strength of Evidence Against

The strength of evidence against the use of learning styles is very strong. To put it simply, using learning styles to design or deploy learning is not likely to lead to improved learning effectiveness. While it may be true that learners have different learning preferences, those preference are not likely to be a good guide for learning. The bottom line is that when we design learning, there are far better heuristics to use than learning styles.

…

The weight of evidence at this time suggests that learning professionals should avoid using learning styles as a way to design their learning events. Still, research has not put the last nail in the coffin of learning styles. Future research may reveal specific instances where learning-style methods work. Similarly, learning preferences may be found to have long-term motivational effects.

…

Debunking Resources — Text-Based Web Pages

- Frequently Asked Questions about Learning Styles by Daniel Willingham, PhD

- Press Release from the Association for Psychological Science

- Myth of Learning Styles by Cedar Riener and Daniel Willingham

- $5,000 Learning Styles Challenge by Will Thalheimer, PhD and others

- eLearn Magazine by Guy Wallace

- Blog Post by Cathy Moore

- Article at Psychology Today

- Blog Post by Daniel Willingham

- Blog Post by Cathy Moore — How to Gently Persuade Believers of Learning Styles.

Learning Styles Or Learning Preference? — from learndash.com by Justin Ferriman

Excerpts (emphasis DSC):

There are fewer buzzwords in the elearning industry that result in a greater division than “learning style”. I know from experience. There have been posts on this site related to the topic which resulted in a few passionate comments (such as this one).

…

As such, my intent isn’t to discuss learning styles. Everyone has their mind made up already. It’s time to move the discussion along.

Learner Preference & Motivation

If we bring the conversation “up” a level, we all ultimately agree that every learner has preferences and motivation. No need to cite studies for this concept, just think about yourself for a moment.

You enjoy certain things because you prefer them over others.

You do certain things because you are motivated to do so.

In the same respect, people prefer to learn information in a particular way. They also find some methods of learning more motivating than others. Whether you attribute this to learning styles or not is completely up to you.

How to respond to learning-style believers – from Cathy Moore

Excerpt:

First, the research

These resources link to or summarize research that debunks learning styles:

- My post Learning styles: Worth our time? summarizes some studies and has extensive discussion in the comments.

- My post How to be a learning mythbuster has links to easy, approachable debunking articles to pass to clients or teammates.

- The Debunking Club has compiled several other resources. This TED talk in particular could be useful for your colleagues and clients.

- Make It Stick: The Science of Successful Learning by Peter C. Brown et al. is a readable summary of research.

- Urban Myths about Learning and Education by Pedro De Bruyckere et al. debunks several myths.

Are Learning Styles Going out of Style? — from mindtools.com by Bruce Murray

Excerpt (emphasis DSC):

Their first conclusion was that learners do indeed differ from one another. For example, some learners may have more ability, more interest, or more background than their classmates. Second, students do express preferences for how they like information to be presented to them… Third, after a careful analysis of the literature, the researchers found no evidence showing that people do in fact learn better when an instructor tailors their teaching style to mesh with their preferred learning style.

The idea of matching lessons to learning styles may be a fashionable trend that will go out of style itself. In the meantime, what are teachers and trainers to do? My advice is to leave the arguments to the academics. Here are some common-sense guidelines in planning a session of learning.

Follow your instincts. If you’re teaching music or speech, for example, wouldn’t auditory-based lessons make the most sense? You wouldn’t teach geography with lengthy descriptions of a coastline’s contours when simply showing a map would capture the essence in a heartbeat, right?

Since people clearly express learning style preferences, why not train them in their preferred style? If you give them what they want, they’ll be much more likely to stay engaged and expand their learning.

Do Visual, Auditory, and Kinesthetic Learners Need Visual, Auditory, and Kinesthetic Instruction? — from aft.org by Daniel T. Willingham

Excerpt (emphasis DSC):

Question: What does cognitive science tell us about the existence of visual, auditory, and kinesthetic learners and the best way to teach them?

The idea that people may differ in their ability to learn new material depending on its modality—that is, whether the child hears it, sees it, or touches it—has been tested for over 100 years. And the idea that these differences might prove useful in the classroom has been around for at least 40 years.

What cognitive science has taught us is that children do differ in their abilities with different modalities, but teaching the child in his best modality doesn‘t affect his educational achievement. What does matter is whether the child is taught in the content‘s best modality. All students learn more when content drives the choice of modality. In this column, I will describe some of the research on matching modality strength to the modality of instruction. I will also address why the idea of tailoring instruction to a student‘s best modality is so enduring—despite substantial evidence that it is wrong.

From DSC:

Given the controversies over the phrase “learning styles,” I like to use the phrase “learning preferences” instead. Along these lines, I think our goal as teachers, trainers, professors, SME’s should be to make learning enjoyable — give people more choice and more control. Present content in as many different formats as possible. Give them multiple pathways to meet the learning goals and objectives. If we do that, learning can be more enjoyable and the engagement/motivation levels should rise — resulting in enormous returns on investment over learners’ lifetimes.

Addendum on 6/17/15:

- Top 10 Reasons to Write a Blog Post Debunking the Learning Styles Myth — from willatworklearning.com by Will Thalheimer

Addendum on 7/14/15:

- New Scientific Review of Learning Styles — from willatworklearning.com

Excerpt:

Just last month at the Debunker Club, we debunked the learning-styles approach to learning design based on our previous compilation of learning-styles debunking resources.

.

Now, there’s a new research review by Daniel Willingham, debunker extraordinaire, and colleagues.

.

Willingham, D. T., Hughes, E. M., & Dobolyi, D. G. (2015). The scientific status of learning styles theories. Teaching of Psychology, 42(3), 266-271. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0098628315589505

From DSC:

Learning is messy. Teaching & learning is messy.

In my experience, teaching is both an art and a science. Ask anyone who has tried it and they will tell you that it’s not easy. In fact, it takes years to hone one’s craft…and there are no silver bullets. Get a large group of Learning Theorists together in the same room and you won’t get 100% agreement on the best practices for how human beings actually learn.

Besides that, I see some issues with how we are going about trying to educate today’s learners…and as the complexity of our offerings is increasing, these issues are becoming more apparent, important, visible, and costly:

- Professors, Teachers, & Trainers know some pieces of the puzzle.

- Cognitive Scientists, Cognitive Psychologists, and Neuroscientists know some other pieces of the puzzle.

- Learning Theorists and Instructional Designers know some other pieces of the puzzle.

- Learning Space Designers know some other pieces of the puzzle.

- And yet other specialties know about some other pieces of the puzzle.

But, in practice, how often are these specialties siloed? How much information is shared between these silos? Are there people interpreting and distilling the neuroscience and cognitive science into actionable learning activities? Are there collaborative efforts going on here or are the Teachers, Professors, and Trainers pretty much on their own here (again, practically speaking)?

So…how do we bring all of these various pieces together? My conclusion:

We need a team-based approach in order to bring all of the necessary pieces together. We’ll never get there by continuing to work in our silos…working alone.

…

But there are other reasons why the use of teams is becoming a requirement these days: Accessibility; moving towards providing more blended/hybrid learning — including flipping the classroom; and moving towards providing more online-based learning.

Accessibility

We’re moving into a world whereby lawsuits re: accessibility are becoming more common:

Ed Tech World on Notice: Miami U disability discrimination lawsuit could have major effect — from mfeldstein.com by Phil Hill

Excerpt:

This week the US Department of Justice, citing Title II of ADA, decided to intervene in a private lawsuit filed against Miami University of Ohio regarding disability discrimination based on ed tech usage. Call this a major escalation and just ask the for-profit industry how big an effect DOJ intervention can be. From the complaint:

Miami University uses technologies in its curricular and co-curricular programs, services, and activities that are inaccessible to qualified individuals with disabilities, including current and former students who have vision, hearing, or learning disabilities. Miami University has failed to make these technologies accessible to such individuals and has otherwise failed to ensure that individuals with disabilities can interact with Miami University’s websites and access course assignments, textbooks, and other curricular and co-curricular materials on an equal basis with non-disabled students. These failures have deprived current and former students and others with disabilities a full and equal opportunity to participate in and benefit from all of Miami University’s educational opportunities.

Knowing about accessibility (especially online and via the web) and being able to provide accessible learning materials is a position in itself. Most faculty members and most Instructional Designers are not specialists in this area. Which again brings up the need for a team-based approach.

Also, when we create hybrid/blended learning-based situations and online-based courses, we’re moving some of the materials and learning experiences online. Once you move something online, you’ve entered a whole new world…requiring new skillsets and sensitivities.

The article below caused me to reflect on this topic. It also made me reflect yet again on how tricky it is to move the needle on how we teach people…and how we set up our learning activities and environments in the most optimal/effective ways. Often we teach in the ways that we were taught. But the problem is, the ways in which learning experiences can be offered these days are moving far beyond the ways us older people were taught.

Why we need Learning Engineers — from chronicle.com by Bror Saxberg

Excerpt (emphasis DSC):

Recently I wandered around the South by Southwest ed-tech conference, listening to excited chatter about how digital technology would revolutionize learning. I think valuable change is coming, but I was struck by the lack of discussion about what I see as a key problem: Almost no one who is involved in creating learning materials or large-scale educational experiences relies on the evidence from learning science.

We are missing a job category: Where are our talented, creative, user-centric “learning engineers” — professionals who understand the research about learning, test it, and apply it to help more students learn more effectively?

…

So where are the learning engineers? The sad truth is, we don’t have an equivalent corps of professionals who are applying learning science at our colleges, schools, and other institutions of learning. There are plenty of hard-working, well-meaning professionals out there, but most of them are essentially using their intuition and personal experience with learning rather than applying existing science and generating data to help more students and professors succeed.

Also see:

- Why you now need a team to create and deliver learning — from campustechnology.com by Mary Grush and Daniel Christian

Excerpt:

“Higher education institutions that intentionally move towards using a team-based approach to creating and delivering the majority of their education content and learning experiences will stand out and be successful over the long run.”

Addendum on 5/14/15:

Thinking different(ly) about university presses — from insidehighered.com by Carl Straumsheim

Excerpt (emphasis DSC):

Lynn University, to further its tablet-centric curriculum, is establishing its own university press to support textbooks created exclusively for Apple products.

Lynn University Digital Press, which operates out of the institution’s library, in some ways formalizes the authoring process between faculty members, instructional designers, librarians and the general counsel that’s been taking place at the private university in Florida for years. With the university press in place, the effort to create electronic textbooks now has an academic editor, style guides and faculty training programs in place to improve the publishing workflow.

From DSC:

Chris uses ecoMOBILE and ecoMUVE to highlight the powerful partnerships that can exist between tools and teachers — to the benefits of the students, who can enjoy personalized learning that they can interact with. Pedagogical approaches such as active learning are discussed and methods of implementing active learning are touched upon.

Chris pointed out the National Research Council’s book from 2012 entitled, “Education for Life and Work: Developing Transferable Knowledge & Skills in the 21st Century” as he spoke about the need for all of us to be engaged in lifelong learning (Chris uses the term “life-wide” learning).

Also, as Chris mentioned, we often teach as we were taught…so we need communities that are able to UNlearn as well as to learn.

Also see:

Teaching in a Digital Age

A.W. (Tony) Bates

Guidelines for designing teaching and learning for a digital age

The book examines the underlying principles that guide effective teaching in an age when everyone, and in particular the students we are teaching, are using technology. A framework for making decisions about your teaching is provided, while understanding that every subject is different, and every instructor has something unique and special to bring to their teaching. The book enables teachers and instructors to help students develop the knowledge and skills they will need in a digital age: not so much the IT skills, but the thinking and attitudes to learning that will bring them success.

As Tony mentions here, his intended audience is primarily:

- college and university instructors anxious to improve their teaching or facing major challenges in the classroom,

- school teachers, particularly in secondary or high schools anxious to ensure their students are ready for either post-secondary education or a rapidly changing and highly uncertain job market.

An example chapter:

Chapter 7: Pedagogical differences between media

- 7.1 Thinking about the pedagogical differences of media

- 7.2 Text

- 7.3 Audio

- 7.4 Video

- 7.5 Computing

- 7.6 Social media

- 7.7 A framework for analysing the pedagogical characteristics of educational media

From DSC:

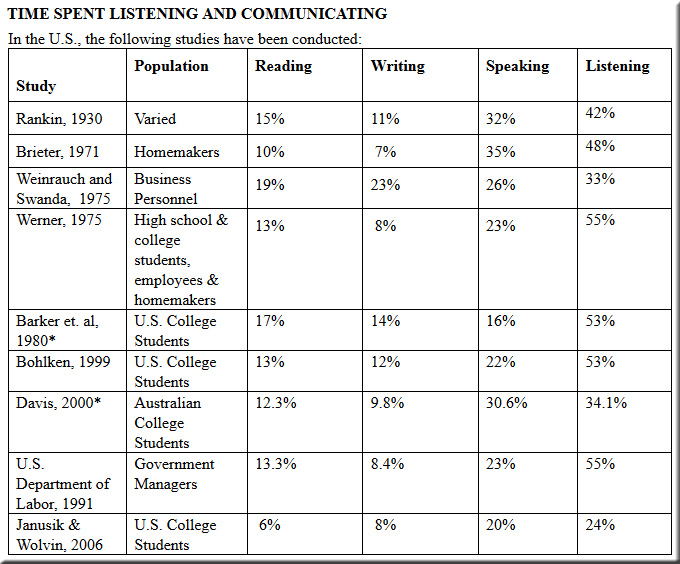

Many K-12 schools as well as colleges and universities have been implementing more collaborative learning spaces. Amongst other things, such spaces encourage communication and collaboration — which involve listening. So here are some resources re: listening — a skill that’s not only underrated, but one that we don’t often try to consciously develop and think about in school. Perhaps in our quest for designing more meta-cognitive approaches to learning, we should consider how each of us and our students are actually listening…or not.

Mackay: The power of listening — from startribune.com by Harvey Mackay

Excerpts:

We are born with two ears, but only one mouth. Some people say that’s because we should spend twice as much time listening. Others claim it’s because listening is twice as difficult as talking.

Whatever the reason, developing good listening skills is critical to success. There is a difference between hearing and listening.

…

These statistics, gathered from sources including the International Listening Association* website, really drive the point home. They also demonstrate how difficult listening can be:

- 85 percent of our learning is derived from listening.

- Listeners are distracted, forgetful and preoccupied 75 percent of the time.

- Most listeners recall only 50 percent of what they have heard immediately after hearing someone say it.

- People spend 45 percent of their waking time listening.

- Most people remember only about 20 percent of what they hear over time.

- People listen up to 450 words per minute, but think at about 1,000 to 3,000 words per minute.

- There have been at least 35 business studies indicating listening as a top skill needed for success.

From the International Listening Association*

LISTENING AND EDUCATION

- Even though most of us spend the majority of our day listening, it is the communication activity that receives the least instruction in school (Coakley & Wolvin, 1997). Listening training is not required at most universities (Wacker & Hawkins, 1995). Students who are required to take a basic communication course spend less than 7% of class and text time on listening (Janusik, 2002; Janusik & Wolvin, 2002). If students aren’t trained in listening, how do we expect them to improve their listening?

- Listening is critical to academic success. An entire freshman class of over 400 students was given a listening test at the beginning of their first semester. After their first year of studies, 49% of students scoring low on the listening test were on academic probation, while only 4.42% of those scoring high on the listening test were on academic probation. Conversely, 68.5% of those scoring high on the listening test were considered Honors Students after the first year, while only 4.17% of those scoring low attained the same success (Conaway, 1982).

- Students do not have a clear concept of listening as an active process that they can control. Students find it easier to criticize the speaker as opposed to the speaker’s message (Imhof, 1998).

- Effective listening is associated with school success, but not with any major personality dimensions (Bommelje, Houston, & Smither, 2003).

- Students report greater listening comprehension when they use the metacognitive strategies of asking pre-questions, interest management, and elaboration strategies (Imhof, 2001).

- Students self-report less listening competencies after listening training than before. This could be because students realize how much more there is to listening after training (Ford, Wolvin, & Chung, 2000).

- Listening and nonverbal communication training significantly influences multicultural sensitivity (Timm & Schroeder, 2000).

* The International Listening Association promotes the study, development,

and teaching of listening and the practice of effective listening skills and

techniques. ILA promotes effective listening by establishing a network of

professionals exchanging information including teaching methods, training

experiences and materials, and pursuing research as listening affects

humanity in business, education, and intercultural/international relations.

10 important skills for active listening — from educatorstechnology.com

Excerpt:

Effective Listening — with Tatiana Kolovou and Brenda Bailey-Hughes — from lynda.com

Course description:

Listening is a critical competency, whether you are interviewing for your first job or leading a Fortune 500 company. Surprisingly, relatively few of us have ever had any formal training in how to listen effectively. In this course, communications experts Tatiana Kolovou and Brenda Bailey-Hughes show how to assess your current listening skills, understand the challenges to effective listening (such as distractions!), and develop behaviors that will allow you to become a better listener—and a better colleague, mentor, and friend.

Topics include:

- Recalling details

- Empathizing

- Avoiding distractions and the feeling of being overwhelmed

- Clarifying your role

- Using attentive nonverbal cues

- Paraphrasing what was said

- Matching emotions and mirroring

How to stop talking and start listening to your employees — from inc.com by Will Yakowicz

As a leader, you’re bound to be talking a lot, but you can’t forget to give others a chance to speak their mind.

—————————

Addendum on 2/13/15:

- Wake-up call: How to really listen — from irishtimes.com by Sarah Green

Insights from the Harvard Business Review into the world of work

Excerpt:“It can be stated, with practically no qualification,” Ralph Nichols and Leonard Stevens wrote in a 1957 article in Harvard Business Review, “that people in general do not know how to listen. They have ears that hear very well, but seldom have they acquired the necessary aural skills which would allow those ears to be used effectively for what is called listening. ”

In a study of thousands of students and hundreds of business people, they found that most retained only half of what they heard – and this immediately after they had heard it. Six months later, most people only retained 25 per cent.

…It all starts with actually caring what other people have to say, argues Christine Riordan, provost and professor of management at the University of Kentucky.

Listening with empathy consists of three specific sets of behaviours.

Rhizomatic, digital habitat – A study of connected learning and technology application — from researchgate.net by Thomas Kjærgaard & Elsebeth Korsgaard Sorensen, Institute of Philosophy and Learning, Aalborg University, Denmark

Keywords:

Rhizomatic learning, connectivism, digital habitat, inclusion, cooperative learning, community of practice.

1.0 Introduction

It is fair to claim that today’s college classrooms are technology rich; in our case almost every student brings his/her own laptop, smartphone and maybe tablet-computer to class every day. It is our experience that the technology richness doesn’t always contribute to the learning process, especially in presentation-oriented, teacher-centered teaching. The majority of the activities carried out on the computers are substituting paper based alternatives. In our case the technologies only rarely redefine the pedagogic design or the students’ behavior. The students in this study almost never use blogs (0%), social bookmarking (6%), twitter (0%) or multimodal note taking on smartphones. So they generally copy analogue behavior to the digital world. We believe that with the web-technology at hand today the possibilities for redefining the pedagogic design and the students learning processes are many. Because of that this study was designed as a synthesis of partially an attempt to redefine the utilization of digital tools according to their affordances, and partially to study a networking community of practice in a college classroom (Sorensen & Dalsgaard 2008). By combining digital tools that aspire to have great potential in teaching and learning activities that utilize the network structures that the students know already form their private lives we hope to make a strong connection that will generate a powerful pedagogic design. Furthermore the technology will show its general equity as more than just a note taking tool.

…

6.0 In conclusion

In the six classes that participated in this small study it seemed that many benefitted from the new technology-based way of collaborating. But it is still only a few groups that really worked as communities of practice in digital habitats, it seems that only very few possessed ‘network literacy’. Our survey showed that the students were not used to thinking of the internet as a place for not only searching information but also for processing information. The survey says that in the childhood homes of the students computers were used for entertainment (64%) and games (84%) and only 12% used computers for forums and blogs etc. Maybe we can’t use their childhood experiences with computer usage to explain their adult usage of computers in general but there is a connection between those students who come from families where internet forums and blogs were used to process information and those students current network literacy. The problem is that only three students came for such families, hence the foundation for stating anything general is way too insecure.

It would be interesting to investigate why some groups worked as communities of practice and why others didn’t. Unfortunately that was not within the scope of this study but it might be in future studies. It could seem like the groups that became communities of practice were the ones where the group members already knew how to learn in networks and which knowledge that was appropriate to ‘store’ in their group peers.

This notion, if it is meaningful on a larger scale, is similar to what Rheingold calls network literacy (Rheingold 2012).

Is the term ‘homo conexus’ describing the evolution of the homo sapiens into at more networking more knowledge sharing, more co-creating being? It seems to be what the literature on the field predict (Bay 2009, Rheingold 2012, Castells 2005, Siemens 2005). However in our small study it didn’t seem to be the case. We saw a glimpse of ‘homo conexus’ in some groups but the conclusion is that there is still quite a long way from the connected, networking homo conexus of the literature to an average student in our classes. The study shows that working in a technology rich, rhizomatic classroom demanded a lot form both teachers and students.

- First and foremost both students and teachers have to acknowledge the principals of the rhizomatic approach. The pedagogic design must present a map of possibilities and not a fixed route. This is in itself a challenge for some students.

- Then students and teachers have to be literate in the technologies.

- Then students and teachers have to acknowledge that mastering learning is an important part of learning.

- Then students and teachers have to understand and accept their new position in the learning process and in the didactic design

If those circumstances are present then the rhizomatic, digital habitat seems to be an interesting pedagogic design that could be investigated further. If we look at isolated instances (the Tabby Lou story, Gee 2012) it is evident that almost anything can be learned if you master learning in at network and that potential should be utilized in teaching.

Trying to solve for the problem of education in 2015 — by Dave Cormier; with thanks to Maree Conway for her posting this on her University Futures Update

Excerpt:

The story of the rhizome

The rhizome has been the story i have used, frankly without thinking about it, to address this issue. There are lots of other ways to talk about it – a complex problem does not get solved by one solution. In a rhizomatic approach (super short version) each participant is responsible for creating their own map within a particular learning context. The journey never ‘starts’ and hopefully never ends. There is no beginning, no first step. Who you are will prescribe where you start and then you grow and reach out given your needs, happenstance, and the people in your context. That context, in my view, is a collection of people. Those people may be paying participants in a course, they may be people who wrote things, it could be people known to the facilitator. The curriculum of the course is the community of people pulled together by the facilitator and all those others that join, are contacted or interacted with. The interwebs… you know.

…

The point here is that i attempt to replace the ‘certainty of the prepared classroom’ with the ‘uncertainty of knowing’. In doing so I’m hoping to encourage students to engage in the learning process in their own right. I want them to make connections that make sense to them, so that when the course is over, they will simply keep making connections with the communities of knowing they have met during the class. The community is both the place where they learn from other people, but, more importantly, learning how to be in the community is a big part of the curriculum. Customs, mores, common perspectives, taboos… that sort of thing.

Excerpt:

As it turns out, the difference between novices and experts in a wide variety of fields can be attributed to a single trait, the trait that prompts great writers to consider their readers: the ability to step outside of yourself.

…

Cognitive scientists called this new element of expert performance metacognition–the ability to think about thinking, to be consciously aware of oneself as a problem solver, and to monitor and control one’s mental processing.

…

Metacognitive practices help us become aware of their strengths and weaknesses as learners, writers, readers, test-takers, group members, etc. A key element is recognising the limit of one’s knowledge or ability and then figuring out how to expand that knowledge or extend the ability. Those who know their strengths and weaknesses in these areas will be more likely to “actively monitor their learning strategies and resources and assess their readiness for particular tasks and performances.”

- Thinking About Thinking: Reflection and Metacognition — from heutagogycop.wordpress.com by Stewart Hase

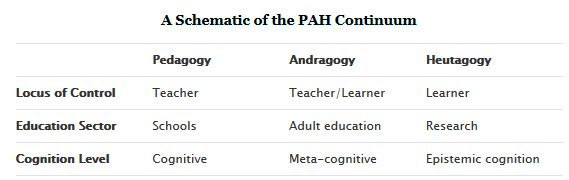

The PAH Continuum: Pedagogy, Andragogy & Heutagogy — from heutagogycop.wordpress.com by Fred Garnett

Excerpt:

Excerpts:

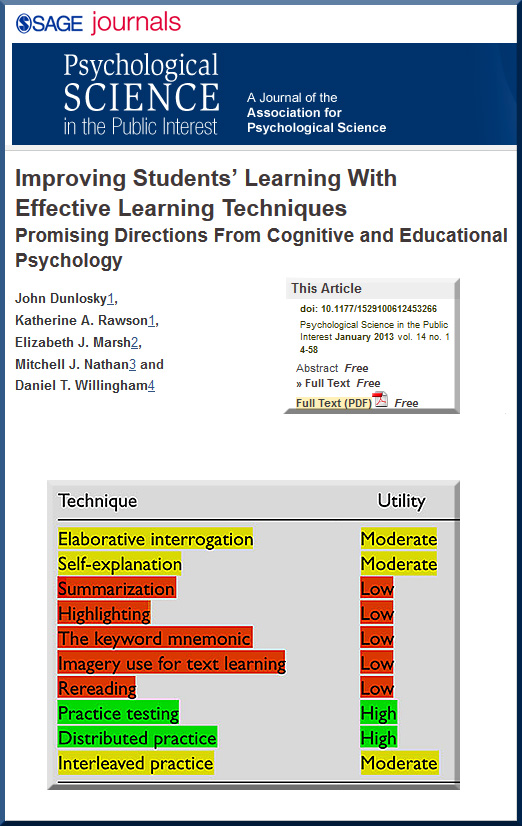

In this monograph, we discuss 10 learning techniques in detail and offer recommendations about their relative utility. We selected techniques that were expected to be relatively easy to use and hence could be adopted by many students. Also, some techniques (e.g., highlighting and rereading) were selected because students report relying heavily on them, which makes it especially important to examine how well they work. The techniques include elaborative interrogation, self-explanation, summarization, highlighting (or underlining), the keyword mnemonic, imagery use for text learning, rereading, practice testing, distributed practice, and interleaved practice.

To offer recommendations about the relative utility of these techniques, we evaluated whether their benefits generalize across four categories of variables: learning conditions, student characteristics, materials, and criterion tasks. Learning conditions include aspects of the learning environment in which the technique is implemented, such as whether a student studies alone or with a group. Student characteristics include variables such as age, ability, and level of prior knowledge. Materials vary from simple concepts to mathematical problems to complicated science texts. Criterion tasks include different outcome measures that are relevant to student achievement, such as those tapping memory, problem solving, and comprehension.

…

Our hope is that this monograph will foster improvements in student learning, not only by showcasing which learning techniques are likely to have the most generalizable effects but also by encouraging researchers to continue investigating the most promising techniques. Accordingly, in our closing remarks, we discuss some issues for how these techniques could be implemented by teachers and students, and we highlight directions for future research.

Also see:

- Sense-making Skills — from Harold Jarche <– with my thanks to Harold for posting this; this is where I got this item from

- The lesson you never got taught in school: How to learn! — from bigthink.com by Neurobonkers

Here Comes Generation Z — from bloombergview.com by Leonid Bershidsky

Excerpts:

If Y-ers were the perfectly connected generation, Z-ers are overconnected. They multi-task across five screens: TV, phone, laptop, desktop and either a tablet or some handheld gaming device, spending 41 percent of their time outside of school with computers of some kind or another, compared to 22 percent 10 years ago. Because of that they “lack situational awareness, are oblivious to their surroundings and unable to give directions.”

Members of this new generation also have an 8-second attention span, down from 12 seconds in 2000, and 11 percent of them are diagnosed with attention deficiency syndrome, compared to 7.8 percent in 2003.

Also see Sparks & Honey’s presentation:

From DSC:

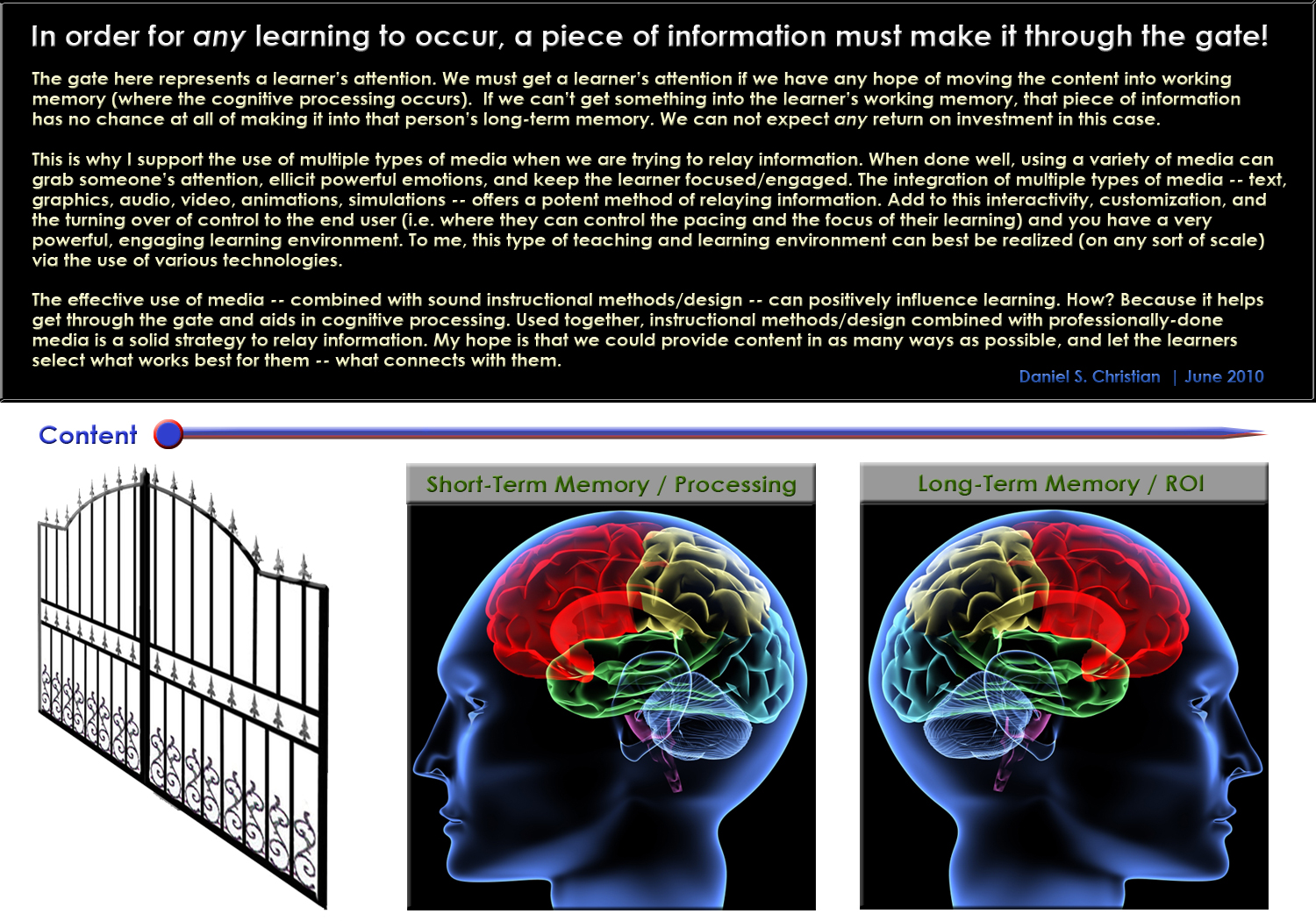

I have been wondering about the possibility that gaining students’ attention is becoming harder and harder to do. The above items seem to confirm that attentions are, in deed, shrinking. We must get through “the gate” (i.e., getting someone’s attention) if we want to have a chance of getting something into someone’s long term memory.

So what should professors, teachers, and trainers do?

For me, this is where things like active learning, project-based learning, and real-world learning come in. Highly relevant, hands-on learning where we turn over more control to the student, helping them own their own learning. We need to provide more choices as to how students can meet the learning objectives.

More choice. More control. Tap into their passions and internal motivations, introduce more play and more opportunities for students to display and cultivate their creativity.

The following article also has some solid thoughts/ideas that seem very relevant for this topic:

- The Science of Attention: How To Capture And Hold The Attention of Easily Distracted Students — from opencolleges.edu.au by Saga Briggs

Excerpt from section entitled, “Tricks for Capturing Your Students’ Attention“:

1. Change the level and tone of your voice.

Often just changing the level and tone of your voice – perhaps by lowering or raising it slightly – will bring students back from a zone-out session.

.

2. Use props or visuals.

Presenting a striking picture related to your topic is sure to get all eyes on you. Don’t comment on it; allow students to start the dialogue. Here are a few resources on how to use animations and storyboards as a teaching tool.

.

3. Make a startling statement or give a quote.

Writing a surprising statement or quote related to the content on the board has a similar effect. In a lesson about linebreaks in poetry, write, “I am dying” on the board, wait a minute, and continue on the next line with “for a bowl of ice cream.” See what kind of reaction you get.

.

4. Write a challenging question on the board.

…

Why Educators Need to Know Learning Theory — from onlinelearninginsights.wordpress.com by Debbie Morrison

This second post focuses on learning theory and how it applies to not only course design, but educators’ role in creating excellent learning experiences for their students.

Excerpt:

We need to study learning theory so we can be more effective as educators. In this post I bridge the gap between learning theory and effective educators; describe why we need to start at A to get to B. I also describe how a grasp of learning theory translates to knowledge of instructional methods, that moves educators towards creating optimal learning environments. Post one of this series described optimal learning environments in the context of a framework that includes three dimensions of resources. Post three will include scenarios of institutions applying the principles of the framework, and in this post we take a step back to examine briefly the underpinnings of pedagogical methods.

From DSC:

Debbie Morrison writes a solid postings here. Thanks Debbie!

During my Masters in Instructional Design for Online Learning (at Capella University), I took a course on learning theories. What struck me from the readings/discussions regarding learning theories were that:

- Though all of the learning theories have their place and serve to contribute valuable pieces to the field, there is no silver bullet — and you will find no agreement amongst teachers, professors, learning theorists, cognitive psychologists, others as to thee learning theory of choice

.

- Instructional Designers, teachers, professors, trainers can’t always recall which theory says what, who are the chief proponents/inventors of the theories, and how those theories are supposed to translate into educating others

So I applaud Debbie’s boiling these theories down and providing some characteristics of instructional methods associated with the various theories.

I like how she concludes her posting:

Is one set of instructional methods better than the other? No—and this is the crux of the post, that there is a variety of methods that serve different learning needs. It’s the skilled and intuitive educator that analyzes a learning situation, leverages the resources at his or her disposal (as per the Learning Design Framework) and is able to analyze the situation and design the very best learning experience for his or her student.

Though we humans constantly try to put things into neat little boxes to explain everything, at the end of the day, learning is still messy. Teaching is both an art and a science. And it’s tough. A good teacher is both very valuable and very skilled.

Also see:

- Theories related to Connectivism — from halfanhour.blogspot.com by Stephen Downes

A somewhat related item — and an item that illustrates how difficult teaching really is:

Stop motivating kids — from ltojconsulting.com by Lee Jenkins

Excerpt:

Children are born motivated to learn, and almost every one of them comes to kindergarten still motivated.

Our job as educators regarding motivation is twofold:

- Do everything possible to maintain motivation and enthusiasm for learning, and

- when a child has lost enthusiasm, work to restore the original motivation.

Our attempts to motivate through incentives are not working. I estimate that the typical American student receives over 10,000 incentives from kindergarten through grade 12. My estimate comes from five incentives per day times 180 school days times 13 years.

George Siemens Gets Connected — from chronicle.com by Steve Kolowich

Excerpts (emphasis DSC):

He earned the most of his college credits at the University of Manitoba but also took courses from Briercrest College and Seminary, a Christian institution in Saskatchewan.

Through Briercrest, Mr. Siemens had his first experience with distance education: He took a Greek-language course that involved studying pronunciation from cassette tapes that came in the mail.

…

When he was 28, he went on a religious retreat. “If you’re always moving away from something, you’ll be lost,” Mr. Siemens remembers a priest telling him. “Always be moving toward something.”

…

The idea behind the first MOOC was not to make credentialing more efficient, says Mr. Siemens. It was to make online instruction dovetail with the way people actually learn and solve problems in the modern world. He and his colleagues wanted “to give learners the competence to interact with messy, ambiguous contexts,” he wrote, “and to collaboratively make sense of that space.”

…

Education, then, is “a connection-forming process,” in which “we augment our capacity to know more” by adding nodes to our personal networks and learning how to use them properly.

From DSC:

This last sentence speaks to a significant piece of why I titled the name of this blog Learning Ecosystems. Such nodes can be people — such as parents, pastors, teachers, professors, coaches, mentors, authors, and others — as well as tools, technologies, schools, experiences, courses, etc. These ecosystems are fluid and different for each of us.

I’m also very glad to see George continuing to lead, to innovate, to experiment and for others to realize the value in supporting/encouraging those efforts. He is out to create the future.

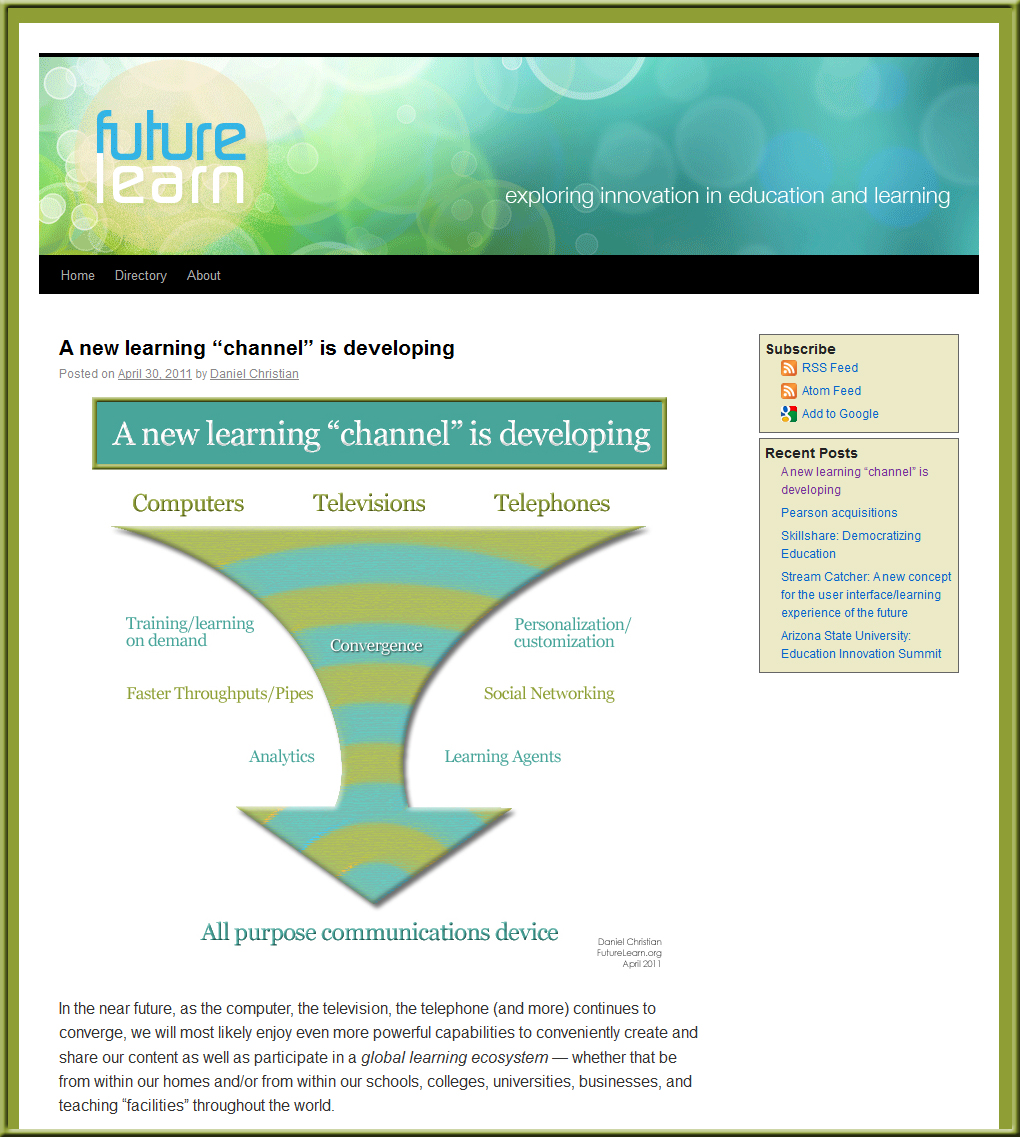

Speaking of being out to create the future, I got involved with one of the experiments he led a while back called future learn: exploring innovation in education and learning. Though that experiment was later abandoned, it helped me crystallize a vision:

That vision has turned into:

![The Living [Class] Room -- by Daniel Christian -- July 2012 -- a second device used in conjunction with a Smart/Connected TV](http://danielschristian.com/learning-ecosystems/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/The-Living-Class-Room-Daniel-S-Christian-July-2012.jpg)

So thanks George, for your willingness to encourage experimentation within higher education. Your efforts impacted me.

Finally, I’m glad to see the LORD continuing to bless you George and to work through you…to change the world.